Previous Issues Volume 9, Issue 1 - 2024

Infection Control Challenge: Kocuria rhizophila Bacteremia from A Peripherally Inserted Central Venous Catheter in A Pediatric Oncology Patient

Arjun Kachhwaha1, Arushi Gupta2,*, Karthik Kumar3, Balram Ji Omar2, Uttam Kumar Nath1

1Department of Medical Oncology Hematology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India

2Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India

3Institute of Child Health and Hospital for Children Madras Medical College, Chennai, India

*Corresponding author: Dr Arushi Gupta, Junior Resident, Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India, Email: [email protected]

Received Date: July 16, 2024

Published Date: September 19, 2024

Citation: Kachhwaha A, et al. (2024). Infection Control Challenge: Kocuria rhizophila Bacteremia from A Peripherally Inserted Central Venous Catheter in A Pediatric Oncology Patient. Mathews J Cancer Sci. 9(1):49.

Copyrights: Kachhwaha A, et al. © (2024).

ABSTRACT

Kocuria rhizophila is a widespread gram-positive bacterium from the family Micrococcaceae, within the order Actinomycetales. Among several species, Rhizophila is known for causing infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, typically leading to bloodstream infections. The patient in question had been diagnosed with B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and was hospitalized in the hematology ward to undergo induction chemotherapy. During a prolonged hospital stay, following chemotherapy, the patient experienced severe complications, including grade IV febrile neutropenia, sepsis, and septic shock. A blood culture taken from the patient's PICC line revealed the presence of Kocuria rhizophila. The patient was treated conservatively, completed the induction chemotherapy, and was eventually discharged in hemodynamically stable condition.

KEYWORDS: B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B cell ALL), Infection Control, Kocuria rhizophila, Pediatric Oncology, PICC (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter), Septic Shock.

INTRODUCTION

Catheter-related bloodstream infections are a significant concern, particularly among patients with haematological malignancies who require prolonged use of PICC (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter) lines for administering chemotherapeutic drugs [1,2]. This extended use often leads to such complications. Infections caused by Kocuria rhizophila, a gram-positive coccus are not as common as catheter-related bloodstream infections [3]. Typically, it exists as a commensal organism on the skin and mucous membranes. Recently, this organism has been identified as a cause of opportunistic infections in immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with haematological malignancies, including patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplants and have indwelling catheters like PICC lines or dialysis catheters [1,4]. Treatment typically involves removing the source of infection, such as the indwelling devices, and administering parenteral antibiotics guided by antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. In situations where device removal is not feasible, such as in resource-limited settings like in our case, antimicrobial lock therapy for the indwelling devices may be used.

CASE SUMMARY

A 14-year-old male patient with no known co-morbidities was admitted to the haematology department with intermittent episodes of fever and bilateral flank pain for the last 2 months associated with nausea and loss of appetite. There were no bleeding manifestations or burning micturition. After sanitising the area with 70% isopropyl alcohol, about 5-10 mL of blood from adults and 1-5 mL from paediatric patients were drawn into blood culture bottles at the patient's bedside while aseptic procedures were followed. Bottles were promptly sent for culture to the microbiology lab. Blood cultures were processed automatically (BD Phoenix BACTEC) [5]. As soon as the blood culture bottle arrived at the lab, it was put straight into the BD Phoenix, a completely automated blood culture system that looks for blood growth. Conventionally, the isolate was identified microbiologically using a Gram stain and culture by aerobic incubation at 37 °C for 18-24 hours, followed by subculturing on chocolate agar, 5% sheep blood agar, and MacConkey agar plates [6,7].

Automated next-gen identification of isolates was done with the VITEK 2 system and simultaneously using MALDI-TOF MS (Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption-Time of flight Mass Spectrometry). Mass spectra were collected using a linear positive MALDI-TOF MS spectrometer (Microflex, Bruker Daltonics) [5,7].

MR (Magnetic Resonance) urography was done and revealed bilateral moderate hydronephrosis with intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy with a large lesion in the left kidney. The patient underwent bilateral D-J stenting. A hemogram showed bi-cytopenia with leucocytosis. Peripheral blood showed blasts and later immunophenotyping by flow cytometry established the diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). The Patient was started on chemotherapy as per ALL-BFM (modified Berlin-Frankfurt-Muenster 2009 protocol).

The patient underwent bone marrow aspiration, conventional karyotyping and multiplex PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction). The patient was diagnosed with B cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and all relevant routine investigations were done (Table 1-5). During the induction chemotherapy, the patient experienced Grade-IV febrile neutropenia and septic shock. The PICC line was removed, and a right-sided central venous catheter was placed in the internal jugular vein. Parenteral antimicrobials and blood products were administered. After the patient's blood count recovered and further chemotherapy was needed, another PICC line was inserted. Once again, the patient developed febrile neutropenia, which responded to parenteral antibiotics (Piperacillin-Tazobactam and Teicoplanin) along with antibiotic lock therapy for the PICC line. Blood cultures indicated the presence of Kocuria rhizophila (Figures 1-3).

The patient was discharged with the PICC line in place for ongoing chemotherapy. There were no further episodes of febrile illness up to the last follow-up, and the patient continued chemotherapy through the same PICC line.

Table 1. Hematological parameters on admission

|

COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT |

VALUES |

|

Hemoglobin |

8.8 g/dL |

|

Total leucocyte counts |

7040/µL |

|

Differential leucocyte counts (%) |

Neutrophil (61.1) |

|

lymphocyte (20.6) |

|

|

eosinophil (0) |

|

|

basophil (0.3) |

|

|

monocyte (18) |

|

|

Differential leucocyte count |

Blast / atypical cells - 15 %, |

|

Platelet counts |

269000/ µL |

|

PERIPHERAL BLOOD SMEAR |

FINDINGS |

|

RBCs |

Mild anisocytosis with normocytic normochromic to microcytic hypochromic RBCs. |

|

WBCs |

|

|

LIVER FUNCTION TEST |

VALUES |

|

Total Bilirubin |

0.49 mg/dL (0.3 - 1.2) |

|

Direct Bilirubin |

0.13 mg/dL (0 - 0.2) |

|

SGPT |

19 U/L (0 – 35) |

|

SGOT |

40 U/L (0 – 35) |

|

ALP |

228 U/L (30 – 120) |

|

GGT |

86 U/L (0 – 38) |

|

Serum Total Protein |

6.2 g/dL (6.6 - 8.3) |

|

Serum Albumin |

2.5 g/dL (3.5 - 5.2) |

|

Serum Globulin |

3.7 g/dL (2.5 - 3.2) |

|

KIDNEY FUNCTION TEST |

VALUES |

|

Blood Urea |

74 mg/dL (17 – 43) |

|

Serum Creatinine |

2.49 mg/dL (0.55 - 1.02) |

|

Serum Na+ |

135 mmol/L (136 – 146) |

|

Serum K+ |

4.30 mmol/L (3.5 - 5.1) |

|

Serum Cl- |

104 mmol/L (101 – 109) |

|

Serum Total Calcium |

7.8 mg/dL (8.8 - 10.6) |

|

Serum Uric Acid |

5.9 mg/dL (2.6 – 6) |

|

Phosphorus |

2.5 mg/dL (2.5 - 4.5) |

|

Viral markers |

HBsAg: negative Anti-HCV antibodies: non-reactive Anti-HIV antibodies: non-reactive |

|

Baseline blood and urine culture |

Sterile |

|

Blood culture during febrile neutropenia (peripheral blood) |

Escherichia coli (sensitive to Piperacillin- Tazobactam and meropenem) (Resistant to colistin) |

|

Throat swab culture during febrile neutropenia |

Klebsiella pneumoniae (Resistant to Piperacillin- Tazobactam and meropenem) (Intermediate resistant to colistin) |

|

Blood culture during febrile neutropenia (2 consecutive blood samples) |

Kocuria rhizophila |

HCV: Hepatitis C Virus

HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen

Figure 1. Kocuria is a Gram-positive cocci arranged in pairs, short chains, tetrads, cubical packets of eight and irregular clusters as seen on gram stain in 100x oil immersion lens.

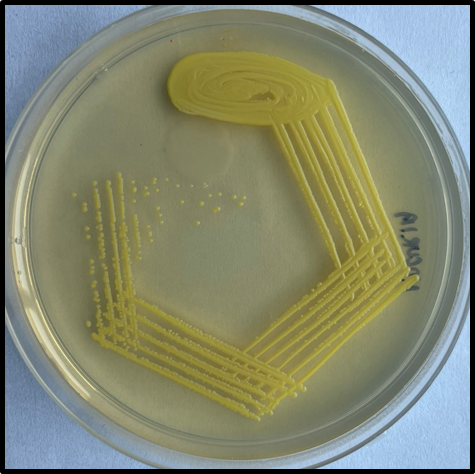

Figure 2. Kocuria spp form 2-3 mm whitish, small, round, raised, convex colonies on initial isolation after 48 hours of aerobic incubation at 37 degrees Celsius, and might develop non-diffusible yellowish pigmentation after prolonged incubation.

Figure 3. Kocuria spp displaying non-diffusible yellowish pigmentation on nutrient agar after 48 hours of aerobic incubation at 37 degrees Celsius.

DISCUSSION

Kocuria rhizophila is often mistaken for coagulase-negative staphylococcus or deemed as a laboratory contaminant [6,7]. Notably, it poses a significant risk to immunocompromised individuals, paediatric patients, and those with implanted medical devices, although rarely affecting those with a robust immune system [8,9]. This bacterium is accountable for a range of infections, including catheter-related bloodstream infections, peritoneal catheter-associated peritonitis, dacryocystitis, endophthalmitis, brain abscess, septic arthritis, and infective endocarditis [10-14]. Given the limited data on antibiotic susceptibility and treatment duration, the recommended approach involves using antibiotics typically employed for staphylococcus infections. [15-18]. The patient received treatment according to our institutional policy, which involved administering parenteral antibiotics and antibiotics lock therapy using Gentamicin and Vancomycin. The child responded well to the treatment and was discharged home later. Due to the limited prevalence and awareness of this organism, there is insufficient data on the optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy. It is worth noting that different cases have been managed with device removal or with intravenous antimicrobial therapy, and antimicrobial lock therapy of the catheter, based on clinician preferences and resource availability in the case of staphylococcus infection. This infection requires immediate treatment as it can rarely lead to life-threatening infections and metastatic abscesses, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.

CONCLUSION

The case emphasizes the importance of recognizing and treating Kocuria rhizophila infection, particularly in vulnerable patient populations. The successful treatment of the patient with parenteral antibiotics and antibiotic lock therapy using Gentamicin and Vancomycin serves as a testament to the importance of swift and appropriate intervention. However, the limited understanding of this organism underscores the need for further research into optimal antimicrobial therapy duration and management approaches. It is crucial for healthcare providers to remain vigilant and consider Kocuria rhizophila as a potential pathogen in susceptible patient populations to ensure timely and effective treatment.

STANDARD OF REPORTING

CARE guidelines and methodology were followed to conduct the study. (“How Much Vitamin D is Too Much? A Case Report and Review of the Literature”)

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent has been taken from the patient.

FUNDING

None.

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Declared none.

REFERENCES

- Nakata M, Kuji H, Toishi T, Inoue T, Kawaji A, Matsunami M, et al. (2024). Relapsing Peritoneal Dialysis-Associated Peritonitis due to Kocuria rhizophila: A Case Report. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 14(1):10-14.

- Živković Zarić RS, Pejčić AV, Janković SM, Kostić MJ, Milosavljević MN, Milosavljević MJ, et al. (2019). Antimicrobial treatment of Kocuria kristinae invasive infections: Systematic review. J Chemother. 31(3):109-119.

- Becker K, Rutsch F, Uekötter A, Kipp F, König J, Marquardt T, et al. (2008). Kocuria rhizophila adds to the emerging spectrum of micrococcal species involved in human infections. J Clin Microbiol. 46(10):3537-3539.

- Moissenet D, Becker K, Mérens A, Ferroni A, Dubern B, Vu-Thien H. (2012). Persistent bloodstream infection with Kocuria rhizophila related to a damaged central catheter. J Clin Microbiol. 50(4):1495-1498.

- Joyanes P, del Carmen Conejo M, Martínez-Martínez L, Perea EJ. (2001). Evaluation of the VITEK 2 system for the identification and susceptibility testing of three species of nonfermenting gram-negative rods frequently isolated from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 39(9):3247-3253.

- Barberis C, Almuzara M, Join-Lambert O, Ramírez MS, Famiglietti A, Vay C. (2014). Comparison of the Bruker MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry system and conventional phenotypic methods for identification of Gram-positive rods. PLoS One. 9(9):e106303.

- Zhang Y, Hu Q, Li Z, Kang Z, Zhang L. (2023). Kocuria species: an underappreciated pathogen in pediatric patients-a single-center retrospective analysis of 10 years' experience in China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 107(4):116078.

- Rudolph WW, Gunzer F, Trauth M, Bunk B, Bigge R, Schröttner P. (2019). Comparison of VITEK 2, MALDI-TOF MS, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing for identification of Roseomonas mucosa. Microb Pathog. 134:103576.

- Taher NM. (2022). Kocuria species: Important emerging pathogens in pediatric patients. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 16(1):2874-2879.

- Dotis J, Printza N, Stabouli S, Papachristou F. (2015). Kocuria species peritonitis: although rare, we have to care. Perit Dial Int. 35(1):26-30.

- Kim Y, Kim TS, Park H, Yun KW, Park JH. (2023). The First Case of Catheter-related Bloodstream Infection Caused by Kocuria rhizophila in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 43(5):520-523.

- Ziogou A, Giannakodimos I, Giannakodimos A, Baliou S, Ioannou P. (2023). Kocuria Species Infections in Humans-A Narrative Review. Microorganisms. 11(9):2362.

- Nguyen A, Allison RZ, Maynard K, Patterson J. (2018). Kocuria rhizophila Intracerebral Abscess in Diabetic Ketoacidosis. J Neuroinfect Dis. 9(1):275.

- McAleese T, Ahmed A, Berney M, O'Riordan R, Cleary M. (2023). Kocuria rhizophila prosthetic hip joint infection. J Surg Case Rep. 2023(8):rjad484.

- Pierron A, Zayet S, Toko L, Royer PY, Garnier P, Gendrin V. (2021). Catheter-related bacteremia with endocarditis caused by Kocuria rhizophila. Infect Dis Now. 51(1):97-98.

- Mukherjee B, Sheerin A, Anand AR. (2022). Kocuria rhizophila Dacryocystitis Report of a Rare Causative Organism in a Common Clinical Condition. TNOA J Ophthalmic Sci Res. 60(1):57-59.

- Biswal D, Kaur R, Satija S, Seth A, Rathi A, Kant L. (2023). The expanding spectrum of human infections caused by Kocuria species in paediatric patients: One-year observational, prospective hospital-based study. Int J Infect Dis. 130(Suppl_2):64.

- Purty S, Saranathan R, Prashanth K, Narayanan K, Asir J, Sheela Devi C, et al. The expanding spectrum of human infections caused by Kocuria species: a case report and literature review. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2(10):e71.

.png)

.png)