Previous Issues Volume 1, Issue 1 - 2018

Dyspareunia and Sexual Dysfunction during Postpartum Period and Related Factors: A Longitudinal Study

Sema Üstgörül, Emre Yanikkerem*

Associate. Professor, Obstetric and Gynaecologic Nursing, Celal Bayar University Faculty of Health Sciences Manisa/Turkey. Corresponding Author: Emre Yanikkerem, Associate. Professor, Obstetric and Gynaecologic Nursing, Celal Bayar University Faculty of Health Sciences Manisa/Turkey, Tel: 02362330904-5840; Email: [email protected] Received Date: 13 Sep 2018 Accepted Date: 06 Nov 2018 Published Date: 12 Nov 2018 INTRODUCTION Reduced sexual activity and dysfunctional problems are highly prevalent during pregnancy [1] and many women experience sexual dysfunction following childbirth [2]. Sexual function after childbirth is an important component of life [3, 4]. There are many changes in the genital or other body organs of women due to birth which can cause sexual dysfunctions [3]. Perineal trauma, especially obstetric anal sphincter injury, is an independent predictor of dyspareunia one year after the delivery [3]. Women experience many changes during pregnancy and the postpartum period such as physical and physiological problems, changes in the body due to hormonal reasons, adaptation to motherhood and new roles in the family all of which can affect women’s sexual life [5-9]. In the postpartum period, women may have to deal with psychological and physical problems such as breast problems, fatigue, pain in the perineal area, infection, constipation, hemorrhoids, urinary or fecal incontinence, postpartum depression and discomfort during sex [10, 11]. As expected, the problems may affect the women’s sexual life negatively and can cause sexual dysfunction or dyspareunia [8, 12]. Dyspareunia is defined as persistent or recurrent genital pain that occurs before, during or after the sexual intercourse [13], and causes marked distress or interpersonal conflicts [13]. In several studies, it has been determined that breastfeeding, type of delivery, perineal injury and feeling pain during sexual intercourse in the prenatal period were the most important risk factors for dyspareunia in the postpartum period [14, 15, 16]. Dyspareunia can have a significant impact on a woman’s psychological, physical health and body image [13], and can affect her and her partner’s quality of life and sexual relationships [5, 16, 17]. Published studies indicated that dyspareunia prevalence at 6 months postpartum was 45% in Norway [18], 40.7% in Belgium [3], 21.2% in Pennsylvania [19]. In Australia, 24% of women reported dyspareunia at 18 months postpartum [20]. In Lebanon, 67% of women reported experiencing pain during postpartum period [17] and 30.1% of women in Thailand reported dyspareunia at 3 months [21]. In Turkey, dyspareunia in the postpartum period varies between 23.6% and 91.0% in studies in which the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale was used [6, 14, 22]. Sexual health is a special issue that should be certainly assessed by health care professionals. Sexual history, current sexual life and health conditions of couples should be examined while evaluating the sexual function to be able to help couple’s current problems [23]. However, evaluating couple’s fears, knowledge, attitudes and concerns related to sexuality are so very important factors in determining a couple’s sexual problems and understanding of the changes in sexuality during postpartum [9, 24]. As is known, sexuality is still accepted as a taboo in some countries. In the literature, it has been pointed out that health professionals give only information about the resumption of sexual intercourse after delivery and that couples obtain limited information about sexual problems [6, 14]. The number of longitudinal studies evaluating women’s sexual life after delivery in Turkey is not many [6, 14, 15, 22]. Therefore, the aim of the present longitudinal study was to investigate dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction at the third, sixth and ninth months postpartum and related factors. MATERIALS AND METHODS Design and Sample The universe of the study consisted of 468 women in the postpartum period registered to 11 Family Health Centers in Manisa city center according to the data released by the Health Directorate of Manisa in 2013. Sampling size was calculated as 232 in the Epi Info 2000 program with a 5% margin of error and 95% confidence interval based on the unknown prevalence of 50%. During the second and third interviews, one woman got divorced and 11 women were not reached by telephone. Therefore, the study was completed with 220 women who agreed to participate, who had healthy babies, were at the 3rd month postpartum and resumed sexual activities at the third month after delivery. Of the women, those who had multiple pregnancies, placenta previa, placental abruption, bleeding, pregnancy/delivery or postpartum complications, underwent hysterectomy, gave birth through assisted vaginal delivery and had diagnosis of psychological disorders were excluded from the study.

Figure 1: Data flow diagram of the longitudinal study

QUESTIONNAIRE The data of the study were collected with the questionnaire which included two parts. The first part questioned the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics such as age, education, employment status and income status, and health-related characteristics such as body mass index of women, parity, type of delivery and breastfeeding status of women. The first part of the questionnaire was prepared in accordance with the literature [6, 12, 15, 25]. The second part included the Arizona Sexual Experience ScaleFemale version (ASEX) which was developed by McGahuey et al. (2000) to screen and assess the sexual problems of the participants easily [26]. The adaptation of the scale into Turkish was performed by Soykan 2004. The ASEX has five items: sex drive, arousal, vaginal lubrication/penile erection, ability to reach orgasm, and satisfaction from orgasm. The items are rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 to 6. The minimum and maximum possible scores to be obtained from the scale are 5 and 30 respectively. The higher the score is the lower the sexual function is. A total score ≥11 indicates sexual dysfunction. The ASEX’s Cronbach alpha was found as 0.90 [27]. The questionnaire is added as an Appendix. Data collection The first interview which lasted about 30 minutes was made with the participating women in the family health centers by using the face to face interview technique by the first author and their telephone numbers were obtained. In this stage sociodemographic characteristics questionnaire and ASEX were used. The second and third interviews were performed by telephone at the sixth and ninth months postpartum by using ASEX. Each interview took about 10 minutes on average. Ethics of the study Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Manisa Celal Bayar (date: 26.03.2014/ number: 20478486). The study protocol and consent procedure were approved by the Manisa Directorate of Public Health. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participating women. Statistical analysis The SPSS 15.0 was used in the analysis of the study data. Frequency and summary statistics were calculated for all the variables. After the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to find out whether the groups had normal distribution it was seen that the groups were not homogeneous. Therefore, the relationship between the independent variables of the study and the scores for the overall ASEX was evaluated by using MannWhitney U and Kruskal–Wallis with Bonferroni correction tests. Significant independent variables in the univariate analysis were examined using the multiple regression analysis. In the models, the error term analysis was used to evaluate the data normality, linearity and constant variance (homoscedasticity). There was a significant auto-correlation between the ages of the women, the ages of their husbands and the length of their marriages. Therefore, the ages of their husbands and length of their marriages were excluded from the model. In addition, independent variables and ASEX total scores ≥11 were analyzed with the Chi-square test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. RESULTS The relationship between the characteristics of the women and the ASEX scores were shown in Table 1 and Table 1 continued. In the study, the mean ages of the women and their husbands were 28.6±4.8 (min=18 max=43) and 31.5±5.1 (min=21, max=48) respectively. In the current study, the mean number of deliveries was determined as 2.0±1.2 (min=1 max=9), the mean duration of marriage was 6.3±5.1 (min=1, max=25) years, the mean body mass index of the women was 25.7±4.1 (min=16, max=41) at the third month after delivery (data not shown). Of the women, 20.0% had vaginal delivery, 19.5% had episiotomy, 15.5% had elective caesarean section, 16.8% had emergency cesarean section and 28.2% had recurrent cesarean section (Table 1 continued). The majority of the women breastfed their babies in the third, sixth and ninth months (99.5%, 96.8% and 90.9%, respectively). The most common contraceptive method used by the couples at the third (40.9%), sixth (48.2%) and ninth (45.9%) months postpartum was the male condom. Of the husbands, 7.3% had male sexual dysfunction. Of the male sexual dysfunction, 6.8% was premature ejaculation and 0.5% was satyriasis (excessive or abnormal sexual craving in the male) (data not shown). The mean days of resumption after delivery 46.8±12.3 (min=10, max=100). Overall, 11.8% of the women (n=26) experienced dyspareunia during pregnancy. The prevalence of dyspareunia was significantly more common at the third postpartum month (31.8%) than at the sixth (10.5%) and ninth months (1.8%) (Data not shown). The mean score for the overall ASEX was 15.2±4.1 (min=6, max=28), 12.6±4.3 (min=5, max=23) and 11.0±4.1 (min=5, max=23) at the 3rd, 6th and 9th months after delivery, respectively. The ASEX score (≥ 11) was significantly higher at the third month (87.3%) than at the sixth (66.8%) and ninth months (48.6%) after delivery. The mean ASEX score at the 3rd postpartum month was significantly higher in the women (p=0.006) and their husbands (p=0.032) who graduated from primary school and lower in the women who were married for more than 11 years (p=0.021) and the women who had an arranged marriage. Women who had vaginal delivery obtained high scores from the ASEX at the third month (p=0.061). The mean score of the ASEX was significantly higher in the women who had unplanned pregnancies (17.1±5.2) than in the women who had planned pregnancies (14.9±3.8) (p=0.040). The women who had sufficient sexual knowledge (p=0.002) and the women who thought their partner (p=0.000) was sexually attractive obtained low mean scores from the ASEX (Table 1 and Table 1 continued). The mean ASEX score was significantly higher in the women (p=0.010) and their husbands who were over 31 years of age (p=0.011), who had primary or lower education (p=0.012), who were married for more than 11 years (p=0.034), who had an arranged marriage (p=0.000) and who lived in a rural area (p=0.007) at the 6th month postpartum. Women who were primiparous (p=0.008), received information about sexuality (p=0.042), had sufficient sexual knowledge (p=0.003) and thought their partner was sexually attractive (p=0.000) obtained low scores from the ASEX at the postpartum sixth month (Table 1 and Table 1 continued).

Table 1. Relationship between the characteristics of the participating women and the mean scores they obtained from the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale.

Abbreviation: *Mann Whitney U, **Chi-square test , ***at the third month of postpartum.

Table 1: continued. Relationship between the characteristics of the participating women and the mean scores they obtained from the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale.

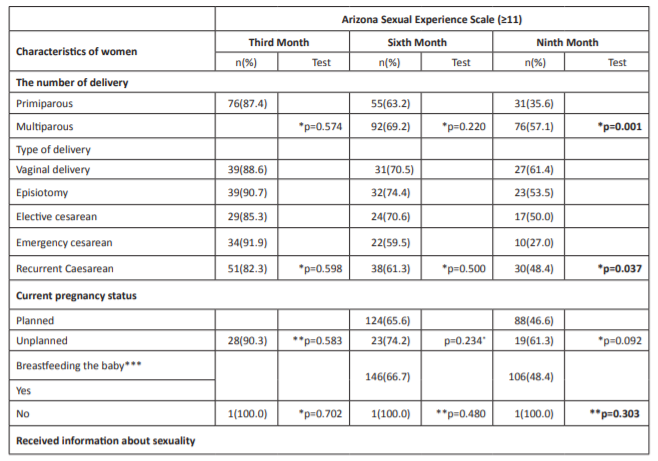

Table 2: Relationship between the characteristics of the participating women and the mean scores they obtained from the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (≥11).

Table 2: continued. Relationship between characteristics of women and the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (≥11).

Abbreviation: *Fisher’s Exact test. ** Chi-square test. ***at third month of postpartum.

The women (p=0.010) and their husbands (p=0.008) who were over than 31 years of age, who had primary or lower education (p=0.001), who were married for more than 11 years (p=0.001) and women who had an arranged marriage obtained significantly higher scores from the ASEX at the ninth month postpartum (Table 1 and Table 1 continued). The women (78.1%) and their husbands (73.2%) who were older than 31 years, had insufficient knowledge about sexuality (79.5%) and thought their husbands were attractive (56.9%) obtained ≥ 11 point from the ASEX at the sixth month postpartum (Table 2 and Table 2 continued). Overall, of the women, 63.3% who were older than 31 years, 56.3% whose husbands were older than 31 years, 58.4% who had primary or lower education, 58.1% who had arranged marriage, 70.8% who did not use any contraceptive methods, 57.1% who were multiparous, 61.4% who had vaginal delivery, 55.9% who had not received any information about sexuality, 71.8 whose knowledge about sexuality was insufficient and 37.5 who thought their husbands were attractive obtained significantly higher scores from the ASEX (≥11) (Table 2 and Table 2 continued). In the regression analysis, it was determined that sexual dysfunction was experienced by the women who thought their knowledge about sexuality was insufficient at three months after delivery, by the women who had an arranged marriage, who had vaginal delivery and who thought their knowledge about sexuality was insufficient at the sixth month and by the multiparous women and women who thought their knowledge about sexuality was insufficient at the ninth month. Providing counseling to women about sexuality after childbirth is important in determining their sexual problems and improving their quality of life. DISCUSSION Postpartum dyspareunia and sexual problems experienced during the postpartum period were investigated longitudinally in Manisa, Turkey for the first time. The study findings can provide data about factors affecting sexual life during the postpartum period and can also provide guidance for healthcare providers to evaluate sexual lives of women then they give antenatal and postpartum care to them. In the current study, 11.8% of the women stated that they experienced pain during sexual intercourse during pregnancy. Similarly, the percentage of women experiencing dyspareunia during pregnancy was 10% in Thailand [21] and 9% in Nigeria [28]. In the present study, at the third postpartum month, it was found that 31.8% of the women had dyspareunia, which was lower than the rate determined in earlier studies conducted in Lebanon (67%) [17] and similar to the one determined in Thailand (30.1%) [21]. Published studies indicate that the dyspareunia rate increased from 21.2% at the 6th week to 67% at the 3rd month [18, 20]. In the study, about one out of ten women (10.5%) experienced dyspareunia at the sixth month postpartum and 1.8% at the ninth month postpartum. Dyspareunia prevalence at the sixth month postpartum was found to range between 21.2% and 45.0% in different countries [3, 17, 18, 21]. In Turkey, 58.3% of the women reported that they experienced dyspareunia in the postpartum period [6]. As is seen in the published previous studies, the prevalence of dyspareunia varies from one country to another. The sexual lives of women should be evaluated in the postpartum follow-ups and the couples experiencing problems should be referred to the relevant units.

In the present study, the ASEX score (≥ 11) was significantly higher at the third month (87.3%) than at the sixth (66.8%) and ninth months (48.6%) after delivery. The results of the present study and other studies indicate that, the risk of sexual dysfunction was higher in the early postpartum stage (0-6 months) [11, 21, 29, 30]. In studies conducted in Turkey, the mean ASEX score was 14.0 [22] and 91.3% of women whose ASEX score was ≥ 11 had sexual problems in the first postpartum year [25]. Sexual health problems are common in the postpartum period but despite this fact, it is a topic that lacks professional recognition. Our findings suggest that women should be asked about their sexual functions during both pregnancy and the postpartum period. Providing training and counseling about changes of sexuality during pregnancy and postpartum period, displaying preventive and curative approaches are very important for the improvement of the sexual health of women. In the present study, older women and their husbands had higher ASEX scores at the sixth and ninth months postpartum, which was similar to findings reported by studies conducted in Germany [1], Turkey [6, 31] and Japan [32]. The relationship between education and sexual dysfunction experienced throughout the postpartum period is unclear in studies. Similar to the findings of other studies [33] our findings showed that women with low educational levels experienced sexual dysfunction at the 3rd, 6th and 9th months after delivery. Contrary to our findings, in some studies, it was found that the age and educational level of women [2, 21, 30, 34] did not affect the women’s quality of sexual life. Older and low educated women may benefit from routine sexual dysfunction screening for early diagnosis and intervention. The postpartum period is one of the periods during which sexual health problems are frequently experienced and puerperal women should be trained on how to cope with sexual dysfunctions, the contact numbers of centers providing services on this subject should be given to couples in written materials and brochures. It should be suggested to women that they can use vaginal lubricants in this period. Our findings determined that the women who were married for more than 11 years or who had an arranged marriage obtained high scores from the ASEX. Contrary to the findings of the present study, Akyüz’s (2009) study did not find any relationship between the duration of marriage and women’s quality of sexual life [31]. In the findings of the present study, no relationship was determined between employment and income status of the women and their ASEX scores. The mean ASEX score at six months after delivery was significantly higher in the women who lived in rural areas. Dyspareunia in the postpartum period was observed more in the women who were unemployed or had low income [14]. On the basis of the results of the present study and studies in the literature, the problems experienced by these women can be detected and treated. These women can also be supported by increasing their educational levels and by providing counseling about sexual life to them. In the present study, primiparous women at the sixth and ninth months postpartum obtained lower scores from the ASEX than did the multiparous women. The relationship between the number of deliveries and sexual problems may be quite complex and contrary to our findings, it was stated in the literature that the number of births given by women did not affect the condition of experiencing sexual problems in the postpartum period [6, 22, 31, 35, 36] or that primiparity was associated with experiencing sexual dysfunction in the postpartum period [1-3, 16, 18, 20]. Parallel to our findings, the rate of incidence of sexual problems was higher in women who gave three or more births [20, 35]. In our findings multiparity was determined as a risk factor for sexual dysfunction at nine months after delivery. The higher the number of children is, the more problematic the sexual lives of spouses is. It may be useful for spouses to spend more time with each other, to talk to each other about the problems they experience. In the present study, there was not any relationship between breastfeeding and ASEX scores. While some studies stated that breastfeeding was associated with experiencing sexual dysfunction in the postpartum period [1, 2, 18, 25], others revealed no association [16, 21]. Breastfeeding is linked to a low coital activity, low sexual desires and low sexual satisfaction of females and their partners. Breastfeeding females start their sexual life later, suffer from dyspareunia more often and get less satisfaction from the sexual intercourse [37]. In the present study, ASEX scores were higher in the women who had unplanned pregnancy only at the 3rd month. Training and counseling about the effective birth control methods can be provided to every woman so that they can have the desired number of children at the desired time. Discussion with couples about the postpartum sexuality and contraception should be part of a routine antenatal and postpartum care in order to prevent unplanned pregnancies and to improve their health seeking behavior. The results of several studies about the relationship between the birth type and postpartum sexual problems are contradictory. While the type of delivery was determined not to affect sexual function in some studies, in some studies, it was stated that higher-degree perineal tears [38], postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction [25] and episiotomies may cause dyspareunia which negatively affected women’s sexual life [21, 39, 40]. Contrary to our findings, in Lebanon, women who had a cesarean section were more likely to have pain during the postpartum sexual intercourse [17]. In the present study, it was found that the mean ASEX score was lower in the women who stated that they received information about sexuality and who thought that their knowledge was sufficient. Providing sexual education to every couple in the antenatal period can decrease sexual problems to be experienced in the postpartum period. In addition, women who thought their partners were sexually attractive obtained low mean scores from the ASEX at the third, sixth and ninth months after delivery. Healthy sexual function after childbirth is one of the cornerstones for couples to evolve from being partners to being parents [25]. In the literature, it was stated that the sexual attraction of spouses to each other may decrease in couples who have long-term marriages [41]. A study in Germany pointed out that low partnership quality was revealed as significant risk factors for sexual dysfunctional problems during postpartum [1]. The patient history should be taken in a nonjudgmental way [13] and clinicians should talk to the couple openly and provide guidance for them on expected changes in sexual health [5]. In the present longitudinal study, postpartum dyspareunia and sexual problems experienced by women during the postpartum period in Turkey were investigated. There were some limitations in the study. First, because the study was carried out in one city, its results cannot be generalized to all women in Turkey. Second, the participating women may have felt embarrassed because the issue is usually perceived as a taboo and therefore the women’s responses may have been biased. Third, sexual functions were evaluated in the study by using the ASEX. In the literature some studies used different scales for evaluating postpartum sexual function. Therefore, we had some difficulties in comparing our findings with those of previously published studies. Despite these limitations, the study has a number of strengths. In conclusion, women who thought their knowledge about sexuality insufficient had sexual dysfunction at the 3rd, 6th and 9th months postpartum. In addition, at the sixth month, the women who had an arranged marriage and vaginal delivery, at the ninth month, multiparous women experienced sexual dysfunction more than did the women in the other groups. Health providers should be aware of the factors that place women at risk for sexual dysfunction most. Open discussions about sexuality during pregnancy and after birth may help reduce the stigma and encourage women to seek help. Thus, women may feel free to talk about the problem and receive specialized help to improve their relationship with their spouses within the marital life.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare no conflict of interest.

APPENDIX Questionnaire 1. How old are you?........... 2. What level of education do you have? a) Primary school or lower b) Secondary school graduate c) High school graduate d) Graduated from university and over 3. How old is your husband?.......... 4. What level of education does your husband have? a) Primary school and lower b) Secondary school graduate c) High school graduate d) Graduated from university and over 5. How long have you been married?............ 6. What is your marriage type? a) Arranged b) Loved 7. Do you have a job? a) Employed b) Unemployed 8. What is your income status like? a) Low income a) Middle income b) High income 9. Where do you live? a) Urban area b) Rural area 10. How much do you weigh?................ 11. How tall are you?................. 12. Do you use any birth control method? a) Yes (Please write down what method of contraception you use?)…………… b) No 13. Have you given birth before? a) Yes b) No 14. How did you deliver your baby? a) Vaginal delivery b) Episiotomy c) Emergency caesarean section d) Elective caesarean section e) Recurrent caesarean 15. Is this pregnancy planned? a) Yes b) No 16. Do you breastfeed your baby? a) Yes b) No 17. Have you received information about sexuality? a) Yes b) No 18. How is your knowledge level on sexual issues? a) Sufficient b) Undecided c) Insufficient 19. Do you think your partner is sexually attractive? a) Yes b) Undecided c) No 20. When did you start postpartum sexual intercourse after delivery? 21. Does your husband have sexual problems? a) Yes (Please write down what sexual problems he has?) b) No

REFERENCES 1. Wallwiener S, Müller M, Doster A, Kuon RJ, et al. (2017). Sexual activity and sexual dysfunction of women in the perinatal period: a longitudinal study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 295(4): 873-883. 2. Rezaei N, Azadi A, Sayehmiri K and Valizadeh R. (2017). Postpartum sexual functioning and its predicting factors among Iranian women. Malays J Med Sci. 24(1): 94-103. 3. Lagaert L, Weyers S, Van Kerrebroeck H and Elaut E. (2017). Postpartum dyspareunia and sexual functioning: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 22(3): 1-7. 4. Amiri FN, Omidvar S, Bakhtiari A and Hajiahmadi M. (2017). Female sexual outcomes in primiparous women after vaginal delivery and cesarean section. Afr Health Sci. 7(3): 623-631. 5. Johnson CE. (2011). Sexual health during pregnancy and the postpartum. J Sex Med. 8(5): 1267-1284. 6. Acele EÖ and Karaçam Z. (2011). Sexual problems in women during the first postpartum year and related conditions. J Clin Nurs. 21(7-8): 929-937. 7. Anzaku AS and Mikah S. (2014). Postpartum resumption of sexual activity. sexual morbidity and use of modern contraceptives among Nigerian women in Jos. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 4(2): 210-216. 8. Escasa-Dorne MJ. (2015). Sexual functioning and commitment to their current relationship among breastfeeding and regularly cycling women in Manila. Philippines. Hum Nat. 26(1): 89-101. 9. Rivas R, Navío J, Martínez M, Miranda LM, et al. (2016). Modifications in sexual behavior during pregnancy and postpartum: Related factors. West Indian Med J. 10: 326- 334. 10. Yee LM, Kaimal AJ, Nakagawa S, Houston K, et al. (2013). Predictors of postpartum sexual activity and function in a diverse population of women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 58(6): 654-661. 11. Barbara G, Pifarotti P, Facchin F, Cortinovis I, et al. (2016). Impact of mode of delivery on female postpartum sexual functioning: spontaneous vaginal delivery and operative vaginal delivery vs. cesarean section. J Sex Med. 13(3): 393-401. 12. Orisaremi TC. (2013). The influence of breastfeeding beliefs on the sexual behavior of the Tarok in north-central Nigeria. Sex Reprod Healthc. 4(4): 153-160. 13. Seehusen DA. (2014). Baird DC. Bode DV. Dyspareunia in women. Am Fam Physician. 90(7): 465-470. 14. Karaçam Z and Çalışır H. (2012). The Prevalence of prepregnancy and postpartum dyspareunia in women giving birth for the first time and related factors. Journal of Anatolia Nurs Health Sci. 15(3): 205-213. 15. Özler A, Evsen MS, Tan P, Turgut A, et al. (2013). Reviewing sexual function after delivery and its association with some of the reproductive factors. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 15(4): 220-3. 16. Costantini E, Villari D and Filocamo MT. (eds.). (2017). Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction (N. Di Donato and R. Seracchioli, Endometriosis and Sexuality) Springer International Publishing Switzerland. 63-77. 17. Kabakian-Khasholian T, Ataya A, Shayboub R and El-Kak F. (2015). Mode of delivery and pain during intercourse in the postpartum period: findings from a developing country. Sex Reprod Health. 6(1): 44-47. 18. Tennfjord MK, Hilde G, Stær-Jensen J, Ellström Engh M, et al. (2014). Dyspareunia and pelvic floor muscle function before and during pregnancy and after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J. 25(9): 1227-1235. 19. Alligood-Percoco, Natasha R, Kjerulff K, Repke JT, et al. (2016). Risk factors for dyspareunia after first childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 128(3): 512-518. 20. McDonald EA, Gartland D, Small R and Brown S. (2015). Dyspareunia and childbirth: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 122(5): 672-679. 21. Chayachinda C, Titapant V and Ungkanungdecha A. (2015). Dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction after vaginal delivery in Thai primiparous women with episiotomy. J Sex Med. 12(5): 1275-1282. 22. Yörük F and Karaçam Z. (2016). The effectiveness of the PLISSIT model in solving postpartum sexual problems experienced by women. AJH. 3 (3): 235-253. 23. Özkan Z and Beji NK. (2014). The effects of psychological and interpersonal factors on sexual function. Androl Bul. 58: 203-208. 24. Bitzer J and Alder J. (2015). Sexuality during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Journal of sex education and therapy. 25(1): 49-58. 25. Serati M, Salvatore S, Siesto G, Cattoni E, et al. (2010). Female sexual function during pregnancy and after childbirth. J Sex Med. 7(8): 2782-2790. 26. McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, Moreno FA, et al. (2000). The arizona sexual experience scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 26(1): 25-40. 27. Soykan A. (2004). The reliability and validity of Arizona sexual experiences scale in Turkish ESRD patients undergoing hemodialysis. Int J Impot Res. 16(6): 531-534. 28. Bello FA, Olayemi O, Aimakhu CO, Adekunle AO, et al. (2011). Effect of pregnancy and childbirth on sexuality of women in Ibadan. Nigeria. Obstet Gynecol. 1-6. 29. Saydam BK, Demireloz AM, Sogukpinar N and Ceber TE. (2017). Effect of delivery method on sexual dysfunction. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 12: 1-5. 30. De Souza A, Dwyer PL, Charity M, Thomas E, et al. (2015). Thomas E. Ferreira CHJ. Schierlitz L. The effects of mode delivery on postpartum sexual function: a prospective study. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 122(10): 1410-1418. 31. Akyüz EO. (2009). Investigation of the postpartum sexual problems and their affecting factors in postpartum (Unpublished Master Thesis). Adnan Menderes University Institute of Health Sciences. Turkey. 32. Song M, Ishii H, Toda M, Tomimatsu T, et al. (2014). Association between sexual health and delivery mode. Sex Med. 2(4): 153-158. 33. Artune-Ulkumen B, Erkan MM, Pala HG and Bulbul Baytur Y. (2014). Sexual dysfunction in Turkish women with dyspareunia and ıts impact on the quality of life. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 41(5): 567-571. 34. Faisal Cury A, Menezes PR, Quayle J, Matijasevich A, et al. (2015). The relationship between mode of delivery and sexual health outcomes after childbirth. J Sex Med. 12(5): 1212-1220. 35. Makki M and Yazdi NA. (2012). Sexual dysfunction during primiparous and multiparous women following vaginal delivery. Tanzan J Health Res. 14(4): 263-268. 36. Adanikin AI, Awoleke JO, Adeyiolu A, Alao O, et al. (2014). Resumption of intercourse after childbirth in southwest Nigeria. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 20(4): 241- 248. 37. Brtnicka H, Weiss P and Zverina J. (2009). Human sexuality during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Bratisl Lek List. 110(7): 427-431. 38. Sayed HAE, Ramadan SS, Ibrahim HA and Moursi HA. (2017). The effect of mode of delivery on postpartum sexual function and sexual quality of life in primiparous women. AJNS 6(4): 347-357. 39. Boran SU, Cengiz H, Erman O and Erkaya S. (2013). Episiotomy and the development of postpartum dyspareunia and anal incontinence in nulliparous females Eurasian. J Med. 45(3): 176 - 180. 40. Persico G, Vergani P, Cestaro C, Grandolfo M, et al. (2013). Assessment of postpartum perineal pain after vaginal delivery: prevalence. severity and determinants. A prospective observational study. Minerva Ginecol 65(6): 669-678. 41. Demir Ö, Parlakay N, Gök G and Esen AA. (2007). Sexual dysfunction in a female hospital staff. Andrology. 33 (2): 156-160.