Previous Issues Volume 9, Issue 2 - 2024

A Case Report for Quality Assurance: Understanding the NSQIP Database and Preventing Error in Peer Review

Katherine A O’Hanlan1,*, Michelle F Benoit2, Alexandra C Thanassi2, Sala J Thanassi2

1Laparoscopic Institute for Gynecology and Oncology, 40 Buckeye, Portola Valley, CA, USA

2Gynecologic Oncology Division of Gynecology Department of Surgery, Palo Alto VA Medical Center, 3801 Miranda Avenue Palo Alto, CA, USA

*Corresponding Author: Katherine A O’Hanlan, Laparoscopic Institute for Gynecology and Oncology, 40 Buckeye, Portola Valley, CA, USA, 94028-8015; Tel: 650-245-3250; Email: [email protected]

Received Date: January 11, 2024

Publication Date: February 09, 2024

Citation: O’Hanlan KA, et al. (2024). A Case Report for Quality Assurance: Understanding the NSQIP Database and Preventing Error in Peer Review. Mathews J Case Rep. 9(2):149.

Copyright: O’Hanlan KA, et al. © (2024)

ABSTRACT

Background: This report assesses the accuracy and applicability of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) and MIDAS data to measure quality in a Gynecologic Oncology service. Method: A retrospective chart review (Canadian Task Force classification II-1) from a community hospital Quality Assurance committee’s evaluation of a Gynecologic Oncology service, assessing all patients undergoing any surgery on the Gynecologic Oncology service from January, 2014 to September, 2017. Results: Surgical data was tabulated from operative notes and office charts. NSQIP data was provided by the hospital Quality Assurance Department’s applications licensed from the American College of Surgeons. Proprietary MIDAS “Inpatient Takeback Rate” was provided by the hospital Quality Assurance Department. Conclusion: Hand-counting of hospital cases provided the most accurate and consistent results. NSQIP data provided variable accuracy in abstraction and coding but was limited to hysterectomy procedures. The MIDAS calculation was broadly inaccurate and should not be viewed as a quality indicator. Misinterpretation of quality data by a QA Department can adversely affect a surgeon’s practice. To further increase the accuracy and utility of the NSQIP database for Oncologic Gynecologists, suggestions for specific queries for Gynecologic Oncology and Gynecology case abstractions are made.

Keywords: Gynecologic oncology; Minimally invasive surgery; complications; laparotomy: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; NSQIP, MIDAS, sham peer review

INTRODUCTION

Quality assessment of surgical services in community hospitals can be challenging. While many community hospitals have initiated surgical quality improvement projects to establish and meet quality benchmark data, misunderstanding of QA data can affect decisions about outcomes. Large data registries have been created to collect clinical information on surgical patients to reliably measure and improve surgical outcomes. In 1994, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) established the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP), a data registry to monitor the rates and correlates of complications for commonly performed General Surgical services in the VA hospitals in which it was initiated [1]. The NSQIP data monitoring algorithm resulted in a dramatic reduction of serious complications from 17.4% to 9.9% and was adopted by many university and community hospitals, and subsequently applied to multiple specialties [2].

NSQIP participation requires trained nursing personnel to abstract data through a detailed chart review process. The data from individual hospitals is submitted for analysis and comparison with national data to obtain meaningful quality feedback for hospitals, practices and surgeons. By 2021, 685 hospitals had contributed data on 983,851 cases enabling creation of quality standards for 14 commonly performed major procedures, including hysterectomy and prolapse support procedures by Gynecology surgeons and services [3]. Demographic data, operative information, established pre-operative risk factors, and 30-day phone follow-up of post-operative complications are submitted on all patients in community and small participating hospitals undergoing hysterectomy and pelvic prolapse surgery [4].

While all specialty-trained Gynecologists learn abdominal and laparoscopic surgeries of the reproductive organs to address pain, bleeding, infections and other conditions, Gynecologic Oncologists (GO) undergo two to four extra years of training to address malignancies originating in the reproductive organs. GO’s also operate on patients who do not have cancer, but whom General Gynecologists may be uncomfortable managing.

Gynecologic cancers metastasize throughout the abdomen and can invade urologic [5,6] intestinal, [7,8] and vascular organs [9] requiring purposeful incision or resection to remove cancer and leave minimal volume of tumor for curative intent [10] These procedures include radical debulking surgeries, hysterectomies, pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomies, intestinal and urologic surgeries and other major procedures that General Gynecologists are not trained to perform [11].

Oncoreductive procedures optimally remove all visible cancer, and can require incidental incisions into bladder, ureter, vasculature, intestines, abdominal wall and other organs. These incisions, incident to the surgical goals, are not accidents, but require careful address and successful repair to restore or maintain normal function. If the repair is inadequate, then the resulting organ breakdown causes immediate sickness, and necessitates a return to surgery. Accidental injuries can also occur during surgery, due to the unplanned puncture or incision of an organ resulting in unplanned emergency repair or a return to surgery.

Counting all components of a surgical encounter can give useful information about a procedure’s risk or surgeon’s skill, but does not discern between accidents and incidents. Two major categories of complications can always be considered accidents: infections [12] and unplanned return to the operating room ROR is also called takebacks [13]. NSQIP coders are instructed to report these two events, as they are obvious evidence of surgical risk. NSQIP coders may not recognize that enterotomy, cystotomy, ureterotomy, and vasculotomy incidental to the primary procedure and successfully addressed should not be considered complications, thus miscode an intended event as a complication. As Gynecologic Oncology knowledge and procedures have advanced, standards have also evolved recognizing that more aggressive surgical dissections that leave no visible residual cancer can have greater potential for prolongation of life and cure [14] commensurate with more frequent complications [15-18].

One advantage of the large NSQIP registry is that surgeons can access the database and extract data on specific procedures or diagnoses to generate outcome information and improve surgical techniques for a specific diagnosis. (e.g. endometriosis, [19] ovarian cancer, [20] endometrial cancer, [21-23] prolapse, [24-26] or procedure (e.g. benign laparoscopic hysterectomy, [27,28] radical hysterectomy, [29] lymphadenectomy, [22,30] or surgical approach (e.g. laparoscopy or laparotomy) [23,31,32] or complication (urologic injury, [33] infection, [34-36] intestinal injury, [37-39] unplanned return to the operating room, [40,41], or cost-accounting [21] by subspecialty service, [16] and more recently for pre-operative risk factors such as frailty index, [42,43] nutrition, [43-45] and body mass index [46,47]. One disadvantage of the NSQIP database is that only hysterectomy cases are included, thereby omitting many major procedures performed on patients who have already had or did not need hysterectomy.

In attempts to describe complications and establish standards of care within the subspecialty, Gynecologic Oncologists have extracted and published Gynecologic Oncology specific data from the NSQIP database by stratifying to include procedure codes performed only by Oncologists (e.g. cancer debulking, bowel resection, or radical hysterectomy; [20,48-51,29]) or only the diagnosis code of a gynecological cancer. [42,48,52,53] (Table 1, in bold) Non-NSQIP retrospective practice data reviews by larger Oncology services [31,54,55] have similarly analyzed and reported their own surgical data for specific oncology diagnoses, procedures or entire services, often using NSQIP-type stratifications. [6,7,15,17,56-61] (Table 1, not in bold) These peer-reviewed manuscripts are retained in the National Congressional Biotechnology Information (NCBI) library and can be obtained for comparison of a local surgeon’s or entire service’s data with NSQIP standards for similar procedures, diagnoses, or services.

Table 1: Publications listing complication data for Gynecologic Oncologist’s practices, using NSQIP data or employing NSQIP-style of data analysis, show overall complication rates for open laparotomy cases ranging from 9 to 37%, with infection rates ranging from 4 to 33%, and serious takeback complications ranging from 4 to 24%. Among the laparoscopy complications in Gynecologic Oncologist’s services overall rates range from 4 to 19%, with infections ranging from 2 to 3.8% and serious take back complications ranging from 2 to 7.4%. Reviewing entire services of Gynecologic Oncologist’s complications overall range from 4.5 to 13.7% with infections ranging from 1.6 to 9%, and serious takeback complications 2.4 to 2.9%.

|

LAPAROTOMY: OVARY/ENDOMETRIAL CANCER CASES |

n |

Any Complication (%) |

Infection (%) |

Serious*/takeback(%) |

|

|

Scalici, 2015, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data |

1269 |

31.2 |

11.2 |

5.5 |

|

Uppal, 2015, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data |

6551 |

3 |

||

|

Rivard, 2016, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data, 60% cancer |

1094 |

33.6 |

15.3 |

19.2 |

|

Rivard, 2016, Gyn Onc |

All debulking + bowel resection |

62 |

61.3 |

14.5 |

40.3 |

|

Patankar, 2016, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data, Ovary Ca, 12% GI surgery |

2870 |

12 |

7 |

10 |

|

Barber, 2017, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data, Ovary Ca, 12% GI surgery |

2806 |

10.9 |

10.9 |

|

|

Bernard, 2020 Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data: All GI surgery/repair |

1058 |

16.9 |

6.1 |

|

|

Bernard, 2020 Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data: No GI surgery/repair |

3907 |

5.7 |

2.9 |

|

|

Narasimhulu, 2020, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data: Ovary Ca |

1434 |

9.1 |

4.5 |

6.1 |

|

Current series Open: 2014-2017 |

Ov Ca: 64% hyst, 67% GI surgery |

90 |

18.9 |

8.9 |

7.8 |

|

Current series Open: 2014-2017 |

Ov Ca: 100% hyst, 66% GI surgery |

58 |

13.8 |

5.2 |

6.9 |

|

LAPAROSCOPY: OUTPATIENT |

n |

Any Complication (%) |

Infection (%) |

Serious*/takeback (%) |

|

|

O'Hanlan, 2007, JMIG |

46% cancer 100% hyst |

830 |

10 |

2 |

4.7 |

|

Hanwright, 2013, O&G |

NSQIP data: 100% hyst, TLH only |

2083 |

6.3 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

|

Lönnerfors, 2015, JMIG |

Randomized trial: 100% hyst, benign |

97 |

19.6 |

6.2 |

|

|

Scalici, 2015, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP data: 100% MIS hyst |

807 |

11.3 |

3.1 |

2.2 |

|

Teoh, 2019 JMIG |

72% Hyst, 35% Staging |

876 |

11.4 |

2.6 |

8.1 |

|

O'Hanlan, 2021, JSLS |

100% hyst, 46% cancer |

2260 |

7 |

1.4 |

2.7 |

|

Current series MIS: 2014-2017 |

Ov Ca: 87% hyst, 21% GI |

67 |

11.9 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

|

Current series MIS: 2014-2017 |

All: 86% hyst, 45% cancer, 11% GI Surgery |

655 |

6.6 |

2 |

2.4 |

|

Current series MIS: 2014-2017 |

All: 100% hyst |

537 |

5.8 |

1.3 |

2 |

|

ENTIRE ONCOLOGY SERVICE |

n |

Any Complication (%) |

Infection (%) |

Serious*/takeback (%) |

|

|

Szender, 2015, IJGC |

NSQIP analysis: Onc service, 46% cancer |

577 |

13.7 |

7 |

2.9 |

|

Uppal, 2016, Gyn Onc |

NSQIP database: any Gyn malig |

12,804 |

15 |

||

|

Current series All, 2014-2017 |

61% hyst, 70% cancer, 13% GI surgery |

762 |

8 |

2.2 |

3 |

|

Current series Hysts: 2014-2017 |

All: 100% hyst |

595 |

5.5 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

*Serious complications are defined by NSQIP as: death, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, progressive renal insufficiency, acute renal failure, pulmonary embolus, deep venous thrombosis, return to the operating room, deep incisional SSI, organ space SSI, systemic sepsis, unplanned intubation, urinary tract infection, or wound disruption.

It is hypothesized that the NSQIP dataset, as currently configured, could be improved to more accurately provide quality comparative data for the various General Gynecologic and Gynecologic Oncology surgeries which range from simple and complex laparoscopy to simple and complex laparotomy, for both benign and cancer diagnoses and procedures. The objective of this article is to examine the community hospital QA file of a GO’s practice and a hospital’s peer review process by comparing and evaluating the accuracy of NSQIP data, hand-counted operative reports, and proprietary hospital software (MIDAS), evaluate the biases that entered into data inaccuracies and peer review procedures, and to generate policy recommendations for improving accuracy and utility in specialty and subspecialty gynecology data reporting.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

With IRB approval from Sequoia Hospital in Redwood City, CA, data was abstracted from hospital and office charts of all surgical patients on a Gynecologic Oncology service from January, 2014 to September 2017 and a copy of each operative report was stored in a locked office file. In preparation for this manuscript, comparison of the operative reports with the surgery schedule was undertaken to confirm thoroughness. Operative report data including demographics, diagnosis, procedures, and complications were uploaded to an Excel spreadsheet. Data from the hospital QA Department, including NSQIP and “MIDAS” data tables, were provided to the surgeon for quality review.

The complication outcomes were categorized using the NSQIP definition of “serious complication” as the presence of any of the following: cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, renal insufficiency and failure, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, return to the operating room (OR), deep incisional surgical site infections (SSI), organ space SSI, systemic sepsis, unplanned intubation, urinary tract infection (UTI), and wound disruption that occurred within 30 days after the surgery.” The ACS NSQIP defines “any complication” as any aforementioned serious complication, superficial incisional SSI, stroke, or ventilator support >48 hours [48]. Each category of complications categorized by NSQIP is more common in a Gynecologic Oncology practice than in a Generalist’s practice due to the higher risk of the patients and the procedures [16].

In this series, “inpatient status” is defined as an “intent to treat” category for those admitted to the inpatient census undergoing a surgery employing a primary vertical midline incision or a Cherney horizontal incision (laparotomy). Outpatients are defined on an “intent to treat” basis, as those patients initially admitted for minimally invasive surgery (laparoscopy) with a planned hospital stay of 23 hours or less, regardless of ultimate duration of stay or “complication”. Consistent with NSQIP standards of categorizing patients by their initial Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedures, patients in this study are categorized as inpatients or outpatients; and the categories do not change, even if an outpatient sustains a complication and is later admitted to or re-admitted to an inpatient census for a prolonged recovery. For accurate comparison of NSQIP data, only the hand-counted operative reports of procedures including hysterectomies from the same time frame are counted. For accurate comparisons of multiple reports over various time-frames, the time-frame of the each of the reports are the same in each table.

RESULTS

Most (70%) of the practice had a malignant diagnosis or indication for an oncologist’s care, similar to other GOs. [62,63] (Table 2) While outpatient laparoscopy was the default approach employed in 86% of all cases, it was also employed in 83% of malignancies. Inpatient laparotomy was employed in 17% of cases, 84% for ovarian cancer debulking, and 16% for removal of massive myomata or suspicious ovarian masses too large for intact removal or for morcellation in laparoscopic bags.

Table 2: Demographics and Diagnoses are stratified by approach.

|

Laparoscopic n = 655 |

Open n = 107 |

Total cases n = 762 |

|||||

|

Demographics |

Mean |

Range |

Mean |

Range |

Mean |

Range |

|

|

Age (years)* |

55.3 |

17-92 |

56.7 |

24-75 |

55.4 |

17-92 |

|

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

29.9 |

14.5-68 |

28.6 |

18-49 |

30 |

14.5-68 |

|

|

Parity (#) |

1.6 |

0-10 |

1.4 |

0-6 |

1.6 |

0-10 |

|

|

Diagnosis |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

Malignant vulvar lesion |

6 |

6% |

6 |

1% |

|||

|

Malignant cervical lesion |

18 |

3% |

18 |

2% |

|||

|

Malignant uterine |

186 |

28% |

8 |

7% |

194 |

25% |

|

|

Malignant adnexal lesion |

69 |

11% |

76 |

71% |

145 |

19% |

|

|

Questionable adnexal mass |

140 |

21% |

140 |

18% |

|||

|

Genetic indications |

32 |

5% |

32 |

4% |

|||

|

Oncologic Diagnosis total |

445 |

83% |

90 |

17% |

535 |

70% |

|

|

Transgender |

18 |

3% |

18 |

2% |

|||

|

Endometriosis |

29 |

4% |

29 |

4% |

|||

|

Benign vulvar |

1 |

1% |

1 |

0% |

|||

|

Benign cervical |

5 |

1% |

5 |

1% |

|||

|

Benign uterine |

117 |

18% |

12 |

11% |

129 |

17% |

|

|

Pelvic issues (pain, prolapse) |

38 |

6% |

4 |

4% |

42 |

6% |

|

|

Other (abscess, fistula) |

3 |

0% |

3 |

0% |

|||

|

Benign diagnosis total |

210 |

93% |

17 |

7% |

227 |

30% |

|

|

All cases / 762 total |

655 |

86% |

107 |

14% |

762 |

100% |

|

Table 3 tabulates 2076 individual procedures that comprised the 762 operative reports for the 44-month duration of the time frame of complications. 1114 individual procedures were Oncology-specific, with 115 indicated bowel procedures performed on 68 of the 107 laparotomy patients, or 64%.

Table 3: All procedures from the operative reports have been abstracted, highlighting over 700 procedures performed only by GOs in bold.

|

Laparoscopic n = 655 |

Open n = 107 |

Total cases n = 762 |

|||||

|

General Procedures |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

Any procedure < Hyst |

64 |

9.8 |

24 |

22.4 |

88 |

11.5 |

|

|

Endometriosis surgery |

5 |

0.8 |

0.0 |

5 |

0.7 |

||

|

Simple hysterectomy |

501 |

76.5 |

25 |

23.4 |

526 |

69.0 |

|

|

Myomectomy |

5 |

0.8 |

4 |

3.7 |

9 |

1.2 |

|

|

Incidental Appendectomy |

167 |

25.5 |

10 |

9.3 |

177 |

23.2 |

|

|

Sacrocolpopexy |

10 |

1.5 |

10 |

1.3 |

|||

|

Cystoscopy |

107 |

16.3 |

3 |

2.8 |

110 |

14.4 |

|

|

Urethropexy |

1 |

0.2 |

2 |

1.9 |

3 |

0.4 |

|

|

Perineoplasty/rectocele |

30 |

4.6 |

4 |

3.7 |

34 |

4.5 |

|

|

Total General Procedures |

890 |

92.5 |

72 |

7.5 |

962 |

48.8 |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Oncologic Procedures |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

Radical hysterectomy, nodes |

32 |

4.9 |

33 |

30.8 |

65 |

8.5 |

|

|

Radical Oophorectomy |

5 |

0.8 |

35 |

32.7 |

40 |

5.2 |

|

|

Omentectomy |

46 |

7.0 |

55 |

51.4 |

101 |

13.3 |

|

|

Enterolysis |

68 |

10.4 |

29 |

27.1 |

97 |

12.7 |

|

|

Vaginectomy |

2 |

0.3 |

11 |

10.3 |

13 |

1.7 |

|

|

Parametrectomy |

3 |

0.5 |

3 |

2.8 |

6 |

0.8 |

|

|

Partial cystectomy |

18 |

16.8 |

18 |

2.4 |

|||

|

Indicated appendectomy |

276 |

42.1 |

47 |

43.9 |

323 |

42.4 |

|

|

Enterotomy |

8 |

1.2 |

13 |

12.1 |

21 |

2.8 |

|

|

Partial enterectomy |

7 |

6.5 |

7 |

0.9 |

|||

|

Partial colectomy |

5 |

0.8 |

36 |

33.6 |

41 |

5.4 |

|

|

Fistula closure |

1 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.1 |

||

|

Exenteration |

|

10 |

9.3 |

10 |

1.3 |

||

|

Partial gastrectomy |

|

2 |

1.9 |

2 |

0.3 |

||

|

Ureterolysis |

39 |

6.0 |

44 |

41.1 |

83 |

10.9 |

|

|

Any Debulking |

8 |

1.2 |

74 |

69.2 |

82 |

10.8 |

|

|

Second look debulking |

11 |

1.7 |

|

|

11 |

1.4 |

|

|

Lymphadenectomy |

29 |

4.4 |

40 |

37.4 |

69 |

9.1 |

|

|

Diaphragmatic/liver debulking |

8 |

1.2 |

30 |

28.0 |

38 |

5.0 |

|

|

Splenectomy |

|

8 |

7.5 |

8 |

1.0 |

||

|

Cholecystectomy |

15 |

2.3 |

5 |

4.7 |

20 |

2.6 |

|

|

Peritoneal port |

|

40 |

37.4 |

40 |

5.2 |

||

|

Panniculectomy |

|

7 |

6.5 |

7 |

0.9 |

||

|

Umbilical Herniorrhaphy |

5 |

0.8 |

|

|

5 |

0.7 |

|

|

Vulvectomy, nodes |

|

6 |

5.6 |

6 |

0.8 |

||

|

Total Oncologic Procedures |

561 |

50.4 |

553 |

49.6 |

1114 |

56.5 |

|

|

Total procedures |

1451 |

69 |

625 |

31 |

2076 |

|

|

CASE REPORT

Peer Review Committee

A community hospital GO was asked by the Chief of Staff (COS) to meet with him for a conversation to help her improve her practice, informing her that she had “increased complications, infections and takebacks.” To prepare, the GO requested a list of her complications, and the rates or data about which they had concerns. The administration provided the medical record numbers of 28 patients, spanning 31 months. The GO hand-counted 588 operative reports in that 31-month retrospective, finding an overall complication rate of (28/588=) 4.8% [13] (Table 4). The 28 complications included 10 SSI, at (10/588=) 2.0%, and 15 ROR at (15/588=) 3.0%. These rates were normative for her subspecialty (Table 1).

Table 4: The top row shows counts of operative reports spanning the 31-month retrospective of the 28 complications, infections and takebacks cases provided by the Chief of Staff in prep for meeting. The two rows below that, show the NSQIP 12-month retrospective data from Figure 1 of “expected” rates of complications, infections and takebacks in the NSQIP hysterectomy-only database of General and Oncology surgeons combined and “actual” NSQIP data collected on the Oncologist. There is no reconciliation between the differences in the absolute numbers, but none are out of the range of publications by other GOs.

|

Total # cases |

Any Complication |

Infection SSI |

Takeback ROR |

|||||

|

n |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

|

31-month retrospective by Oncologist, when called by the Chief of Staff |

||||||||

|

Op Reports - All |

588 |

28 |

4.8 |

10 |

1.7 |

15 |

2.6 |

|

|

12-month retrospective from NSQIP |

||||||||

|

NSQIP cohort “Expected" data from Figure 1 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

|||||

|

NSQIP Surgeon* data from Figure 1 |

254 |

16 |

6.3 |

9 |

3.5 |

9 |

3.5 |

|

|

Op Reports - Hysterectomy-only |

183 |

9 |

4.9 |

3 |

1.6 |

4 |

2.2 |

|

|

Op Reports - All |

227 |

15 |

6.6 |

5 |

2.2 |

8 |

3.5 |

|

|

*From Figure 1: NSQIP identified 254 hysterectomy cases. However, only 227 operative reports including 183 hysterectomy cases were identified through count of operative reports and the Operating schedule. |

||||||||

Figure 1: Screenshot of NSQIP morbidity data for a 12-month period from July 1, 2014 through June 30, 2015, showing 16 complications (6.3%), 9 infections (3.5%) and 9 takebacks (3.5%) out of 254 hysterectomy cases; all normative rates for a Gynecologic Oncologist.

Since 1996, the GO had maintained a spreadsheet of her surgical case data and had published manuscripts describing her laparoscopic data, with total complications ranging from 5.2-10% [64-72] infections varied between 1 and 2%, [65-68,70-72] and ROR ranging from 2.8-4.7% [64-72] (Table 5). She provided the COS this data and also a provided Gynecologic Oncology literature comparison, documenting her practice was comparatively safe.

Table 5: Thirteen publications by the GO assessing surgical complications by procedure or diagnosis showing overall complication rates of 2.3-9.9%, infections at 0-1.9%, and takebacks at 2.2-5.4%.

|

Published |

Focus of laparoscopic surgery |

n |

Any complication % |

Infection SSI % |

Takeback ROR % |

|

2003 O&G |

32% cancer, 100% hyst |

330 |

8.8 |

1.5 |

5.4 |

|

2004 GO |

Oncology TLH, BMI |

90 |

6.7 |

1 |

3.3 |

|

2004 GO |

Oncology TLH, age |

208 |

7.7 |

1 |

2.8 |

|

2005 JSLS |

Uterine cancer: MIS v open |

105 |

5.2 |

0 |

2.6 |

|

2006 GO |

Uterine cancer: BMI |

90 |

6.8 |

1 |

2.2 |

|

2007 JMIG |

Uterine cancer: +/- LND |

112 |

6.3 |

1 |

2.6 |

|

2007 JSLS |

46% cancer 100% hyst |

830 |

9.9 |

2 |

4.5 |

|

2007 JMIG |

Transsexual v Cisgender |

634 |

8 |

0.3 |

4.1 |

|

2011 JMIG |

TLH, uterine size |

983 |

7 |

1.2 |

3.7 |

|

2012 JMIG |

43% cancer, single field prep |

1337 |

n/a |

1.9 |

n/a |

|

2015 GO |

All Aortic LND, MIS v open |

115 |

5.2 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

2016 MIS |

Cuff closure data |

1924 |

2.3 |

1.2 |

1 |

|

2021 JSLS |

46% cancer, BMI |

2266 |

7 |

1.4 |

2.7 |

Ad Hoc Committee

An Ad Hoc Committee (AHC), a subset of the MEC’s peer review committee, was formed to review the GO and met 14 times the ensuing year in closed sessions with a general gynecologist as the committee departmental representative. The GO continued with her usual scheduled surgeries during this time. A patient with an isolated focus of recurrent endometrial cancer adherent to the unirradiated infrarenal aorta underwent surgery planned in advance with a General Surgeon and a Vascular Surgeon [73]. The procedure went well, ultimately requiring the anticipated replacement of the involved segment of the aorta, leaving no residual disease, with a 1,500cc blood loss. A post-operative decision to change a coding/billing modifier, mutually decided by the GO and the General Surgeon, to change from co-surgeon to primary and assistant surgeons, necessitated re-dictation of the original draft dictations. The patient had an uneventful recovery, and remains cured after aortic radiation therapy.

The MEC commenced an investigation of this case as a sentinel event resulting in the summary suspension of the GO’s privileges, calling this case, a “near miss” and the GO’s dictation efforts “dishonest.” A meeting with the Medical Executive Committee to resolve the suspension was unsuccessful. Soon after, the Ad Hoc Committee voted to suspend her. The Medical Board of California and the National Practitioner Database were notified, precluding the GO from seeking privileges at other local hospitals.

Still confidant that an accurate look at her practice data, standards and procedures would show normative rates and competence, the GO appealed for a Judicial Review Committee (JRC), a pseudo-legal trial, as prescribed in the hospital’s bylaws.

Judicial Review Committee

The JRC process required the hospital to provide the Oncologist with her entire Quality Assurance file. These documents, tables and data revealed how the Oncologist’s hospital colleagues, given the misinformation they received, voted for her suspension.

The data from NSQIP and operative report counts:

The files later released to the GO show that initial concerns had been raised about her practice due to a QA computer NSQIP table printout for the 12-months retrospective ending June 30, 2015. (Figure 1) This table showed that among 254 hysterectomy cases (NSQIP only counts cases in which hysterectomy is done), 3.5% had an SSI compared with the NSQIP cohort “Expected” Rate of 1.69%; and a 3.54% ROR compared with the NSQIP cohort “Expected” rate of 1.28%. The figure shows that the comment “Needs improvement” was applied for both SSI and ROR.

Of the 22,658 Gynecologists in the United States [74] 1,157 are GOs [75] or approximately 5%. The NSQIP predominantly benign cohort “Expected” rates of Total, SSI, and ROR between 1.3 and 1.6%, are each far below the known rates in NSQIP Gynecologic Oncology manuscripts listed in Table 1, with 12-55% total complications, 7-9% infections, and 2-19% ROR. [70,72,76,77] It may be reasonable to assume that approximately 95% of the comparator hysterectomies in the NSQIP database are performed by General Gynecologists [16] reinforcing the need compare subspecialists with similar subspecialists, by obtaining peer-reviewed literature establishing standards of care and benchmark complication rates within the subspecialty of Gynecologic Oncology focused on their higher risk patients and higher risk procedures.

A 12-month retrospective hand-count (Table 4) of the operative reports in that duration revealed 183 hysterectomy cases and 227 total (same time frame as the Figure 1 data). Whether counting only hysterectomies or all cases, the Surgeon’s total complication rates of 4.9-6%, SSI rates of 1.6-2.2%, and ROR of 2.2-3.5% were each within all published NSQIP norms for GO practices. (Table 1) Without appropriate data comparisons, the GO was reported to the COS and the Gynecology Department Chair, who requested that the Medical Executive Committee authorize the investigation. It was never evident whether the Gynecology Chair knew that it was inappropriate to compare Subspecialty data with Generalist data. Later evidence to the JRC from both the COS and the CMO revealed that they gave no credence to the submitted Gynecologic Oncology manuscripts and data.

It was found that when the AHC members met, they were provided 628 operative reports from a 36-month retrospective, and had access to the updated list of the GO’s complications, numbering 37 by that time. (Table 6) Her overall complication rate was 5.9%, of which 1.8% had an SSI, and 3.0% had an ROR. The hand-counting of operative reports revealed 658 operations, with the same complication rates as in the Table 1 publications. It remains unclear how the hospital identified 30 fewer operative reports than the hand-counting, and which cases may have been eliminated and why.

Table 6: The 36-month retrospective conducted by the AHC counting 628 operative notes, and the GO’s counts of 658 operative reports with similar rates of complications, infections and takebacks.

|

36-month retrospective |

Any Complication |

Infection SSI |

Takeback ROR |

|||||

|

All cases – AHC |

Total |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

Ad Hoc Committee count |

628 |

37 |

5.9 |

12 |

1.9 |

19 |

3.0 |

|

|

Op Reports – All |

658 |

37 |

5.6 |

12 |

1.8 |

19 |

2.9 |

|

|

44-month retrospective |

||||||||

|

Hysterectomy only: |

Total |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

NSQIP, Figures 3-5 |

484 |

81* |

16.7 |

16 |

3.3 |

14 |

2.9 |

|

|

Op Reports |

595 |

40 |

6.7 |

10 |

1.7 |

12 |

2.0 |

|

|

Inpatient only: |

Total |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

MIDAS |

140 |

26 |

18.6 |

|||||

|

Op Reports – Laparotomy |

107 |

17 |

15.9 |

4 |

3.7 |

7 |

6.5 |

|

|

Outpatient only: |

Total |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

Op Reports – Laparoscopy |

655 |

43 |

6.6 |

10 |

1.5 |

15 |

2.3 |

|

|

All patients: |

Total |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

Op Reports |

762 |

60 |

7.9 |

14 |

1.8 |

22 |

2.9 |

|

*“Any Occurrence” defined by NSQIP includes: superficial incisional surgical site infection (SSI), deep incisional SSI, organ space SSI, wound disruption, pneumonia, unplanned intubation, pulmonary embolus, ventilator >48 hours, progressive renal insufficiency, acute renal failure, urinary tract infection, stroke, cardiac arrest requiring CPR, myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, or systemic sepsis, blood transfusion, vein thrombosis requiring therapy, clostridium difficile, sepsis, septic shock.

The 44-month retrospective shows comparison of NSQIP and hand-counts of hysterectomy-only operative reports all of which are normative to Table 1 data. The MIDAS calculation of return to the operating room at 18.6% is inconsistent with every single NSQIP and hand count at any duration and at any time. The outpatient laparoscopy complications, infections and takebacks are consistent with the Oncologists prior laparoscopic surgery publications, (Table 5) and are normative. The rates of complications from all procedures is 7.9%, with 1.8% infections, and 2.9% takebacks. To evaluate this GO, the QA department reached out to to the ACS-NSQIP office to obtain the comparable Oncology-specific data, but were advised that the Oncology-specific data should be obtained from already published manuscripts, which they viewed as "unavailable."

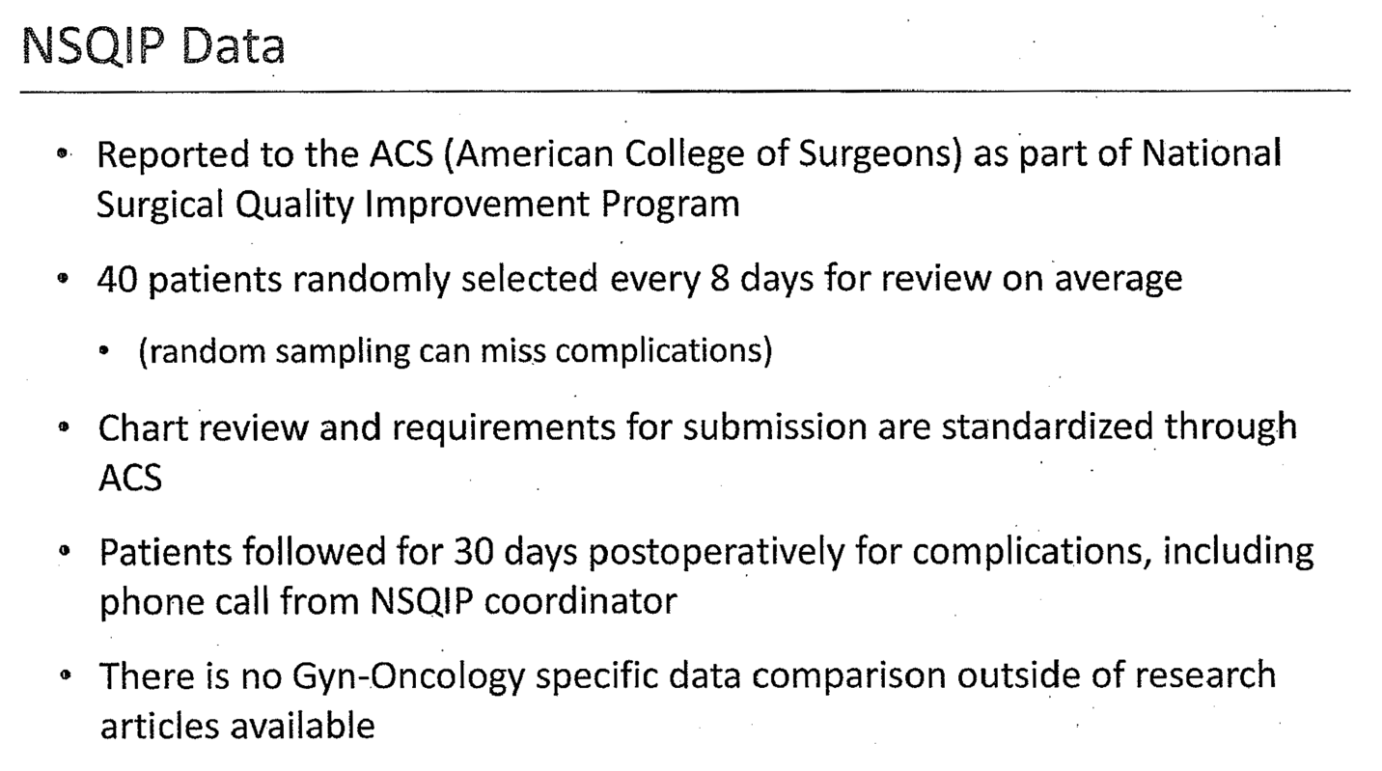

A slide set was created from the NSQIP QA computer printout and was presented by MEC leadership at the AHC and Medical Executive Committee (MEC) meetings. The slides inaccurately described the abstraction process (Figure 2) contradicting the 2017 NSQIP User Guide, [4] and diminished the credibility of the NSQIP data. Specifically, the User Guide states that small and community hospitals will “collect all [hysterectomy] ACS NSQIP-eligible cases at their hospital” (p.6) not “40 patients randomly selected every 8 days for review on average (random sampling can miss complications).” It was inaccurately stated that “There is no Gyn-Oncology specific data comparison outside of research articles,” never obtaining any publicly available NCBI analytic manuscripts. Thus, the GO was compared only with the predominantly benign NSQIP-wide database as listed in Table 1. NSQIP in 2014 also started to stratify procedure by subspecialty gynecology provider, and this subspecialty attribution was not abstracted or presented.

Figure 2: JRC slide with two errors in representation of NSQIP data abstraction methods, incorrectly stating that “There is no Gyn-Oncology specific data comparison outside of research articles available,” thus diminishing NSQIP reliability to hospital reviewers.

The AHC’s next slide showed the NSQIP rates of “Any Occurrence” from 2014 to 2017.4 (Figure 3) The occurrence of any NSQIP adverse event is far more common in a GO practice than in a Generalist practice [78] and “complications” may be due to appropriately aggressive gynecologic cancer surgery, with the goal of no visible residual disease, to include; ventilator use >48 hours, blood transfusion, and urinary tract infection from an indwelling catheter [10]. Annual numbers for “Any NSQIP Occurrences” by the GO were provided, but were not tabulated for rate data (%) to generate an overall understanding. The data calculated by the MEC revealed 81 out of 484 (16.7%) occurrences (reviewing now a 42 month period), which is twice the Generalists’ rate of 9.7%, but compares favorably with NSQIP publications by Gynecologic Oncologists showing 12-55% overall complications in open cases, and 7-19% in laparoscopy cases (Table 1).

Figure 3: Screenshot from the JRC slide presentation showing annual “Any NSQIP Occurrence” rates of 11.7 to 19% compared with the average of 12% in the predominantly benign NSQIP-wide database of 241,567 hysterectomies over the same period. The GO’s data in this table was tabulated in the right-most column added by the author showing (81/484 cases) 16.7% over 42 months, which is normative for Gynecologic Oncologists.

Similarly, the NSQIP tabulated SSI rate of 3.3% (Figure 4, right box) compares favorably with the SSI rates of GOs in Table 1 which ranges from 7-15% for ovarian cancer hysterectomy cases, and 1.4 to 3.8% in laparoscopy hysterectomy cases. These rates are indeed higher than the NSQIP-wide database of 245,971 predominantly benign hysterectomy average of 1.1% (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Screenshot from the JRC slide presentation showing annual NSQIP “Deep Space and Organ SSI” rates of 1.7-5.1 % compared with the average of 1.2% in the predominantly benign NSQIP-wide database of 241,567 hysterectomies over the same period. The GO’s data in this table tabulated in the right-most column added by the author showing (16/484 cases) 3.3% over 42 months, which is normative for Gynecologic Oncologists.

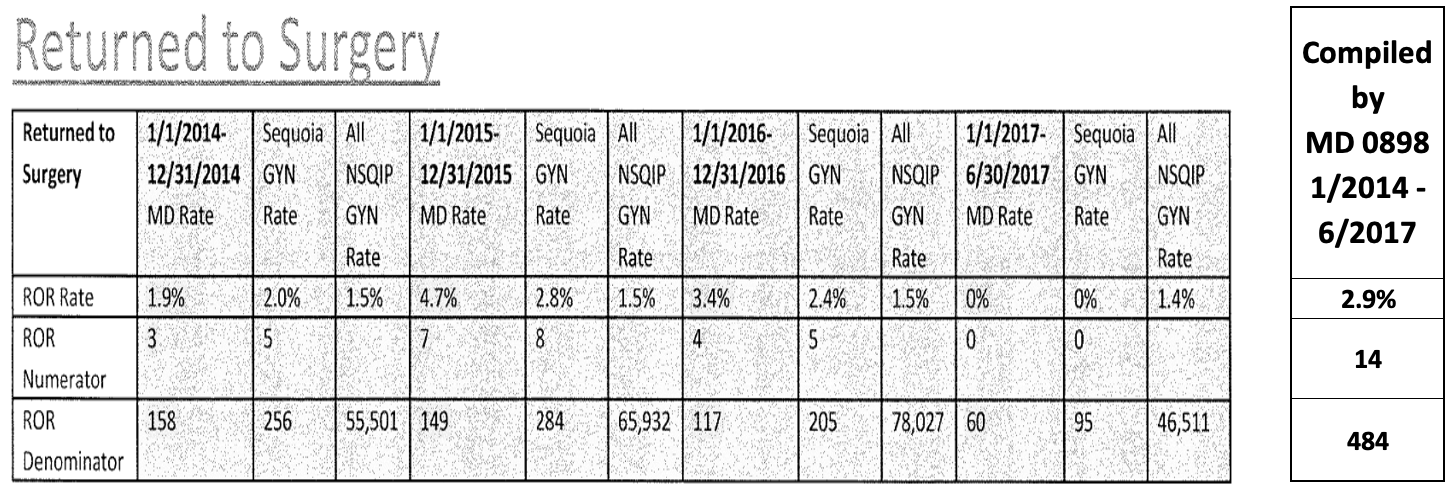

The tabulated ROR rate of 2.9% (Figure 5) is consistent with each of the prior calculations with the data from the Sequoia QA Department, the AHC’s operative report counts, the prior NSQIP rates, and hand-counts of operative reports from all cases and hysterectomy cases by the GO. The ROR of 2.9% is also within range of NSQIP reports of ROR for ovarian cancer cases of 3-19%, 2-9% for laparoscopy cases (Table 1). In Figure 1, the ROR for the predominantly benign NSQIP-wide registry is 1.5%, a much lower rate, and one that is not seen in any NSQIP gynecologic oncology publications.

Figure 5: Screenshot from JRC slide presentation showing annual NSQIP “Returned to Surgery” rates of 1.9-4.7 % compared with the average of 1.5% in the NSQIP-wide database of 241,567 hysterectomies over the same period. The GO’s data in this table is tabulated in the right-most column added by the author showing (14/484 cases) 2.9% over 42 months, which is normative for Gynecologic Oncologists.

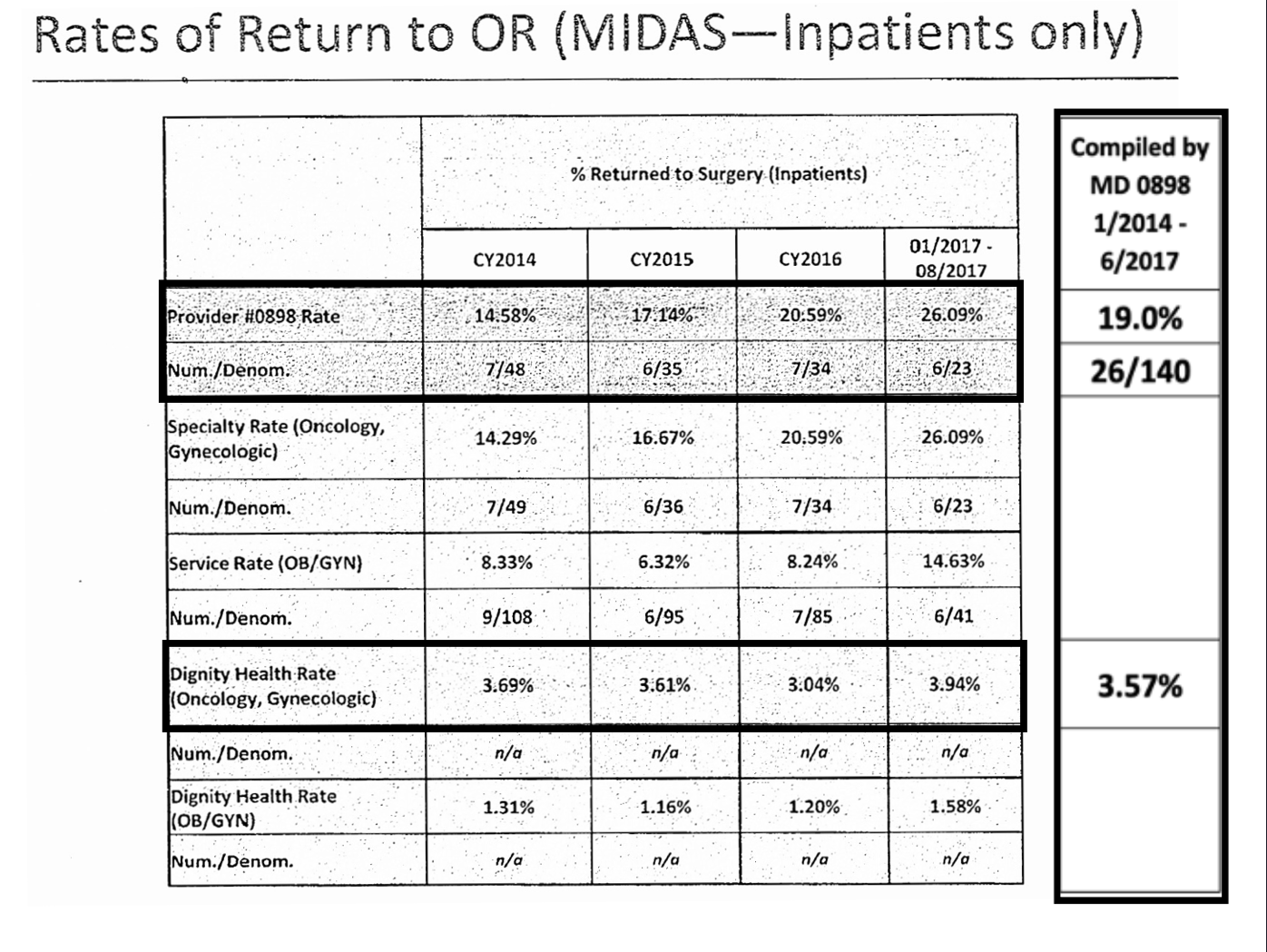

The data from MIDAS “Inpatient Return to OR” versus counted operative reports:

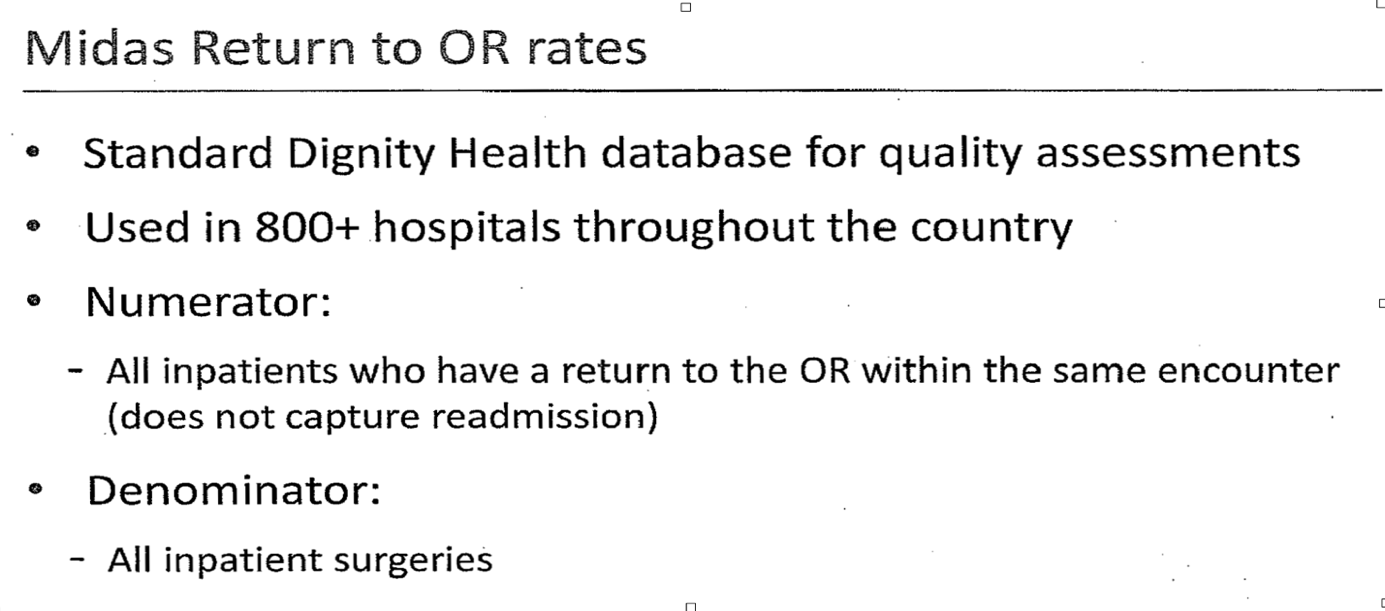

The MEC’s slide deck next introduced the proprietary Dignity Health MIDAS (Conduent® Strategic Performance Management Analytics Solutions) “Inpatient Return to OR” calculation. (Figure 6) The MIDAS data was presented as the “standard for Dignity Health quality assessments”, “used in over 800 hospitals.” The Dignity website reveals that it provides “health care at [only] 39 hospitals …across California, Arizona, and Nevada.” [79] The MIDAS ratio is not a nationally recognized quality indicator and is not a term in the National Congressional Biotechnology Information (NCBI) library. To contrast this, there are over 3,800 NSQIP quality-related manuscripts indexed in the NCBI [3].

Figure 6: Screenshot from CMO slide presentation introducing the MIDAS “Inpatient Return to OR rates.” The MIDAS ratio is not the “Standard Dignity Health database for quality assessments.” It is not “Used in 800+ hospitals throughout the country for quality assesment” The numerator combines both inpatient takeback cases and outpatient takeback cases, divided by the denominator which is comprised of only inpatients.

The MIDAS “Inpatient Return to OR” does not use the standard basic takeback rate formula [13] and is thus not a ROR. According to the slide made by the MEC, the MIDAS “Inpatient Return to OR” calculation numerator is comprised of “all patients, who have a return to the OR within the same encounter,” which combines patients having ROR from both the laparoscopic outpatient service and the laparotomy inpatient service. However, the MEC’s slide shows that, instead of following the standard rate formula and using the same category, all patients, as the denominator, the MIDAS Inpatient ROR denominator uses “All inpatient surgeries.” This anomalous formula results in surgeons with a high outpatient laparoscopic approach rate always having a much higher MIDAS ratio compared to surgeons who directly admit to inpatient, even if they had the exact same complications. The standard rate formula requires that both the numerator and denominator represent patients only in the same category [13].

In Table 7, the annual MIDAS and operative report-counts for inpatient-only takebacks are listed and tabulated for the 44-month retrospective. The MIDAS counts of 26 ROR inpatients and 140 inpatients, and the overall rate of 19% ROR is not supported by the operative notes or the QA data. In a cumulative 44-month retrospective, hospital QA data reveals there were 8 inpatient takeback cases out of 107 laparotomy procedures, ranging annually from 2-4%, with an overall rate of 3%.

Figure 7: Screenshot from JRC showing MIDAS rates for the GO of “ Return to OR rates” at 15-26% compared with the average of 3.5%--miscalculated by denominator case selection. The data in this table was tabulated in the right-most column added by the author showing the effect of this miscalculation at (26/140 cases) 19% over 42 months.

Table 7: The annualized Return to the Operating room data by year with total tabulation combining both both outpatient laparoscopy and inpatient laparotomy, showing the MIDAS calculation to be an outlier, with 7% laparotomy takebacks, and 3% hysterectomy and3% total caseload takebacks. All are normative with publications in Table 1. The NSQIP counting of only hysterectomy cases missed 8 ROR cases for quality review.

|

Inpatient - only cases: |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

1-8/17 |

2014-2017 |

|||||||||||

|

ROR |

Total n |

% |

ROR |

Total n |

% |

ROR |

Total n |

% |

ROR |

Total n |

% |

ROR |

Total n |

% |

||

|

MIDAS |

7 |

48 |

15% |

6 |

35 |

17% |

7 |

34 |

21% |

6 |

23 |

26% |

26 |

140 |

19% |

|

|

Operative report |

3 |

39 |

8% |

2 |

25 |

8% |

2 |

25 |

8% |

0 |

18 |

0% |

7 |

107 |

7% |

|

|

Hysterectomy-only cases: |

||||||||||||||||

|

NSQIP |

3 |

158 |

2% |

7 |

149 |

5% |

4 |

117 |

3% |

0 |

60 |

0% |

14 |

484 |

3% |

|

|

Operative report |

1 |

162 |

1% |

5 |

152 |

3% |

4 |

144 |

3% |

1 |

72 |

1% |

11 |

530 |

2% |

|

|

All cases: |

||||||||||||||||

|

Operative report |

5 |

228 |

2% |

8 |

212 |

4% |

7 |

213 |

3% |

2 |

109 |

2% |

22 |

762 |

3% |

|

There was no member of the AHC or JRC with Oncology or GO certification. Given this, the AHC was compelled to send cases out for review, to a GO subspecialist whom they chose. Of the 7 cases they selected, these cases had been previously adjudicated in monthly departmental QA meetings. When the MEC eventually realized that their data did not show high complications, infections and takebacks, allegations were changed to concerns about severity of the GO’s complications.

The JRC Hearing Officer refused to allow submission of evidence during the proceedings as permitted by the hospital’s bylaws. The Hearing Officer did not require the outside GO reviewer appear for cross-examination. The Hearing Officer was found to be a former hospital consultant with conflict of interest.

Peer testimony was heard from three Anesthesiologists, three Medical Oncologists, a General Surgeon, a Vascular Surgeon, a General Gynecologist and a Gynecologic Oncologist, all with 15+ year working relationships with the Oncologist’s—who all supported that the GO was a competent quality provider. Peer statements affirmed how a takeback rate is legitimately calculated, how NSQIP data was credible with appropriate adjustments to subspecialty and incident/accident “complications” are calculated, how the MIDAS algorithm is flawed, and that subspecialty Gynecologic Oncologists practice data is only appropriately compared with other subspecialists.

The JRC upheld suspension and expulsion of the GO, disregarding proper calculations of/and objective data and due process. At the conclusion of her privileges, she had a 5.4% “any” complication rate, of which 1.7% were SSI and 2.6% were ROR--both by hand-counts and NSQIP data.

DISCUSSION

Accurate reporting of complications is necessary for evaluating quality improvement efforts, documenting standards of care, and providing the source for informed consent. Every hospital has a QA program for peer review that is run by its administrative and medical staff following objective guidelines. The Healthcare Quality Improvement Act of 1986 was implemented to provide necessary immunity to good-faith peer review by local hospital staff [80]. This law empowered local medical staff leaders to conduct peer review processes with federal and state-conferred statutory immunity if hospital bylaws and due process rights were followed. The QA decisions are protected by a judicial system geared to shield the deciders from retaliation--precluding effective oversight of the peer review system.

This case review demonstrates misuse of a registry’s data output from misunderstanding and the misappropriation of the registry in peer review processes. Multiple pitfalls and missteps were identified in this process due to numerous forms of bias. Identification and explanation of these biases then follows.

Reporting and measurement biases

This is reflected in NSQIP event misclassification: Coders and physician reviewers can misclassify purposeful tumor debulking and lymphadenectomy to zero residual disease (R0) as complications, e.g., cystotomy, ureterotomy, vasculotomy. Similarly, enterotomies from lysing symptomatic adhesions, or from obtaining zero-residual disease from cancer resections, will commonly result in an enterotomy rate of 6% [81] e.g. NSQIP does not count organ incisions that are incidental to surgical procedures repaired intraoperatively, but apparently does code accidental injuries that cause a reoperation or other reparative invasive procedure.

NSQIP QA concerns

Correct use and interpretation of the NSQIP data is integral for reliable application. Misapplication can harm the credibility of the registry itself as well as the quality assurance and peer review processes.

- 20 patients not undergoing hysterectomy had complications and were not counted by NSQIP. While these patients were included in the QA Department list of patients, the NSQIP coders did not include them. Consideration of abstracting every major abdominal procedure in Gynecology may give a more accurate complication profile.

- Wound infection is a complication that is accidental to the outcome of surgery. All infections should be tracked and trended, and counted as complications. Of 17 suspected infections, 3 were superficial wound infections, 2 resolved on antibiotics alone, 3 required ROR, and 9 underwent CT drainage of the fluid collection. Standards for managing emergency-room presentation of suspected postoperative fluid collections seen on CT should be established in order to avoid unnecessary CT drainage of noninfected fluid. NSQIP typically requires the results of culture before an abscess can be diagnosed, but these are not uniformly obtained. Surgeons’ infection rates should be within the benchmark for their specialty or procedure, and if higher, then a multipronged investigation should be undertaken to determine whether the prep, equipment, staff, technique or post-operative care can be improved.

- NSQIP does not define whether intestinal obstruction is pre-operative or post-operative and what duration of NPO constitutes an obstruction. A patient in this series complained of constipation, but was coded as obstructed.

- Enterotomy should be categorized as accidental or incidental. If incidental and successfully repaired, then it is not a complication.

- Anastomotic leak is defined and must be confirmed as possibly including “… air, fluid, GI contents, or contrast material. The presence of an infection/abscess thought to be related to an anastomosis, even if the leak cannot be definitively identified as visualized during an operation, or by contrast extravasation, would still be considered an anastomotic leak if this is indicated by the surgeon.”

- NSQIP does not permit acknowledgment of another surgeon’s work or complications. A general surgeon who often assists with gynecologic oncology patients performed three anastomoses, dictated the procedures listing himself as primary surgeon for this portion of the procedure, billed the patient’s insurance for the procedures, and followed the patients until discharge. The NSQIP guidelines for data abstraction require that the data and complications follow patients and procedures but not multiple surgeons. NSQIP does not allow for a complication to be attributed to a specific surgeon if there are more than one surgeon. This system provides for accurate data for assessing the patient's, and the planned procedure's risk, but it can lead to surgeons being blamed for another surgeon’s complications.

- A ureteral leak needs documentation by radiology. CT drainage fluid should be tested for creatinine. Urological obstruction and fistulae could be categorized in the same way as intestinal obstruction with selections to include how it is addressed. Options to ureteral obstruction could be stenting, boari flap, graft, reimplantation, transureteral ureterostomy, percutaneous nephrostomy, no definitive diagnosis. Ureterotomy and cystotomy should be categorized accidental or incidental. If incidental and successfully repaired, then not a complication. Six patients had ureterotomies: two incident to debulking cancer, one was repaired successfully but incorrectly included in the QA list, the other was re-operated, and incorrectly excluded from the QA list.

NSQIP recommendations for optimization

The NSQIP program has been shown to reduce costs and improve quality. The NSQIP survey questions and structured classifications created for coding the General Surgery data do not always apply well to Gynecologic or Gynecologic Oncology surgery. Just as the NSQIP applications have been modified to apply to various surgical specialties, further modifications within the Gynecologic databases can improve the use of the program to achieve its goals of surgical quality, and harm reduction [41]. This case review confirms that NSQIP data is subject to misuse, misinterpretation and misrepresentation, with policy suggestions for correction shown below.

- There can be inconsistency of coding anastomotic leaks as infections. Employing the term “as indicated by the surgeon” for an anastomotic leak allows some subjective component enter into the data input.

- Employing the variables of ileus vs obstruction, instead of prolonged NPO or NGT use will also help distinguish complications vs incidents.

- In major ovarian cancer debulking procedures in which no visible residual is the goal, many Oncologists will perform the cancer resections, and collaborate with General Surgeons for the bowel reconstructive procedures [63]. In these cases, in which the General Surgeon performs, dictates and takes primary responsibility for the intestinal procedure, NSQIP abstractors have no way to attribute the procedure, per se, to the General Surgeon, causing an error of attribution when a complication ensues.

- There should be a designated facility ombudsperson to interpret, represent, and respond to coding and query questions on behalf of the surgeon. This ombudsperson would have deep knowledge of the NSQIP database, access to it, and be a liaison between the surgeon and any review entity that interprets data on behalf of the hospital/administration. This ombudsperson could be regional and should have a stipend, just as coders for the NSQIP program do. This stipend should be built into the program fee in a similar fashion.

- Abstractors may not understand that at times an ROR is planned, resulting in an inaccurate rating of an ROR [41]. It may be necessary for the abstractors to consult a physician or the assigned ombudsman to determine such a plan if it is not obvious.

- Abstractors may not perceive organ incisions and resections as incidental to the primary purpose and success of the surgery (enterotomy, vasculotomy, ureterotomy, cystotomy) and code even successful restorations of the organs as complications. There should be discrimination between incidents in surgery and accidents of surgery. Modifications to the instructions of the NSQIP abstractors can facilitate interpretation of the operative report to aid in classification. Allowing or seeking clarification with the surgeon when an incident is not clear could result in more accurate coding.

- Currently NSQIP abstracts only hysterectomy cases and prolapse surgeries. Because major surgeries do not always involve hysterectomies (prior or declined), and because non-hysterectomy minor surgeries can have severe complications, NSQIP should consider abstracting all abdominal Gynecologic surgeries, coding simply by diagnosis and procedure performed. If NSQIP abstracted all cases performed by Gynecologists, more useful data could be generated for quality assessment and establishment of benchmark standards.

- Some events occurring in the 30-day post-operative period are not due to the surgery. E.g.: Abstractors calling a patient for a 30-day evaluation coded a patient’s complaint that she did not get enough information about post-operative diet and levied her documented chronic constipation as a complication.

- Because participating NSQIP hospitals need to easily perform quality assessments of their General Gynecologists and subspecialty Oncologists or Pelvic Surgeons by comparison of their data only with that of similarly trained surgeons, NSQIP should provide all participating hospitals with complication data stratified a priori by General or subspecialty training of the surgeon, or by procedure code in their semi-annual reports.

Access to self-query for assessment of surgeon’s own quality data within the NSQIP database is advised. Currently, researching surgeons at participating NSQIP hospital can sign a contract and receive complex tables that require statistical programs and advanced data managing to analyze and interpret. Ideally, NSQIP could create templates of complication tables that individual surgeons could select and download that would provide their individual surgical data along with the comparable nationally acquired benchmark data within their subspecialty or by procedure or diagnosis so that motivated surgeons could self-assess and self-improve or more easily publish surgical information.

Hospital QA Process Concerns and Cognitive Biases

Due process is a necessary component of procedural reviews and incorporated into hospital bylaws. Inconsistencies in peer review processes have been denoted “sham peer review.” [82,83]. In a sham peer review, tactics to discredit the provider under review are frequently used and are emphasized in this case report. Features in common with the above peer review and that of a general sham peer review follow:

- Undercoverage bias occurs when a single high performing individual is singled out and not allowed to be represented proportionally. Comparison of a GO with Generalist Gynecology outcomes was not appropriate and using a registry not abstracted for subspecialty also contributed to misperception and misinterpretation.

- Outcome bias is observed when a negative judgment is applied to the appropriate decisions that led to the complication. Complications can ensue absent any error or mistake, especially when cancer-burdened, comorbidity-burdened, elderly, or obese patients are cared for.

- Heuristic availability bias occurred when a historically stable physician was abruptly ascribed numerous questionable performance indicators by a QA team, e.g., with a steady NSQIP complication rate for over 3,500 cases in 15+ years at a hospital. A sudden report of “increased rates of infections, takebacks and complications” should initiate a deeper and thoughtful review with understanding of the data. This data and all full and objective concerns should then be shared directly with the individual surgeon. Any supporting information should be allowed into argument. In this case, the GO could have provided the hospital with the NSQIP publications for comparison of her subspecialty-specific data, and could have explained to them that the MIDAS number was not an ROR formula.

- Framing bias occurred when the leader for the MEC presented the GO as having “higher complications” and as being an “outlier,” allowing the story to proceed in the context they wanted, and thus the other members of the committees did not adjust their perspective to objectively evaluate the situation or its source.

- Anchoring bias occurred when the GO was stated to have higher complication rates, and the committees stayed locked into their early “diagnoses/commitments” despite evidence to the contrary, provided by the GO requesting their re-review of the data.

- The generalist bias: peer reviewers who are not surgeons or are Generalist colleagues, may not know how to interpret surgical data, or apply the data to accurately reflect surgeon quality [84] Because most procedures and complications are distinctive to subspecialty, quality assessments should include the expertise of another same-subspecialist who can accurately testify and respond to queries e.g., the Chair of the Gynecology Department and of the Ad Hoc Committee, both General Gynecologists, did not have subspecialty certifications to adjudicate Oncology complications, but proceeded to do so. Procedurally, these General Gynecologists were low volume surgeons, having admitted that they performed fewer than five laparoscopic hysterectomies in the prior fiscal year. Reviewing panels are required by hospital bylaws to “include at least one member who has the same healing arts licensure and practices in the same specialty as the Practitioner involved”—but this should be specific to subspecialty.

- Conflict of interest: The 3rd party contracted reviewer was paid by the hospital for their services, and in as much, is asked to find in favor of the hospital. Usually, the physician under review can provide 3 names of outside peer reviewers for the committee to choose from.

- Confirmation bias, similar to Lynch mob effect, occurred when a faction or group of physicians gain control of the peer review committee, raise doubt, and defame the provider and their practice with faulty accusations and reports, e.g. the Chair of the Gynecology Department and of the Ad Hoc Committee, both General Gynecologists, knew or should have known that comparisons of the Oncologist’s data with that of the NSQIP-wide database were inappropriate, but none spoke to this issue.

- Competitive financial and surgical interests: Gynecologic Oncologists often perform complicated benign surgery which Generalists may view as a territorial imposition. This may be perceived as “stealing” their cases, yet many General Gynecologists are uncomfortable or inadequately trained to operate on patients that are high-risk, obese, elderly, with many medical comorbidities, or too many prior surgeries, and refer them to the oncologist [16,85,86]. One practice data survey of members of the Society for Gynecologic Oncologists revealed the average Gynecologic Oncologist’s volume consists of 45% benign patients [62] Because of these higher-risk features, these benign patients can experience an expectedly higher rate of complications [16].

- Cognitive bias: This can occur when QA physicians are unaware of a surgeon’s volume and surgical diseases, bias can result from reviewing what appear to be a high absolute number of complications. In so much, complications should not be counted in absolute numbers, but instead as rates; e.g., a surgeon with 10 complications out of 250 surgeries annually, or 4% complications, will have a case for review every month and appear to have excessive complications; while a surgeon with 5 complications performing 50 surgeries annually will have a 10% complication rate but have fewer cases before the monthly QA meeting and not garner suspicion. In this hospital, complications despite pleading by the GO to use opercent rates were counted in absolute numbers , and rates were not applied as described, signaling this surgeon as an outlier despite having normative rates of complications.

- Procedural Bias of Due Process is the procedure set forth for investigations and hearings in each hospital’s bylaws and rules or regulations to ensure justice. Procedural bylaws are intended to protect those on each side of the issue. Yet, a physician unfamiliar with this practice may not identify a hospital lawyer or administrator failing to follow regulations; e.g., denying a physician access to their data and legal representation in the beginning precluded the Oncologist from knowing that their comparisons of her were to generalists, that NSQIP data for subspecialists should be appropriately extracted, and correcting false MIDAS rates. Thus, the investigation was biased ab initio. When bylaws are sidestepped, erroneous review panel decisions can ensue: this includes suppression of evidence, defense testimony, essential witness questioning, and cross-examination; e.g., the expert witness was not made to appear and NSQIP data was suppressed.

- Sampling Bias introduced when a QA process fails to recognize and include credible and relevant information, or lowers the bar for national data validity; e.g., the CMO should have investigated why the MIDAS Inpatient ROR of 19% contrasted dramatically with both the NSQIP and hand-counted rates of 3% from the AHC. In surgical specialties, the ROR is the most important quality assessment data.

- Reporting bias occurs when previously adjudicated or mild grievances can be revived to elevate and prosecute otherwise old or minor infractions into major violations; e.g., from the 28 complications listed at the start of the proceedings against her, 21 had been previously adjudicated as “no issue with physician care,” yet later called “egregious” cases when presented to the JRC.

- Interview bias played a large part in this process when hearsay is accepted without corroboration from patients and nurses; e.g., the QA staff selectively interviewed patients who had complications, elicited complaints, and registered them post hoc. It is a known that patients with complications complain 74% more frequently, [87] especially if solicited by staff. Efforts to label any occurrence as a transgression, actual or assumed, are often used in the hope that something will “stick”.

- Implicit bias: [88] this bias occurs when overt bias cannot be determined and can affect colleagues’ interactions with and perceptions of minority staff. In confidential surveys, 84% of women gynecologic oncologists report a high prevalence of bullying, gender discrimination and microaggressions by their colleagues in medicine [89]. In this case, the readiness of the panels to disbelieve uncontested testimony from multiple peer physicians with years of direct experience with the Oncologist, was in direct contradiction to a single paid consultant who critiqued 7 of 762 patients’ care. While overt sexism, racism or homophobic attitudes are rarely observed, implicit bias against women physicians, [90] physicians of color [91] and homosexual physicians [91,92] has been consistently observed among all physicians and can impede a fair assessment of a minority physician’s skills.

Hospital QA Recommendations:

- QA panels should obtain live testimony from at least one subspecialist for each section at a JRC trial to resolve questions and describe current standards of care.

- Investigations should allow submission of literature evidence during the proceedings and allow time for review of established literature.

- An ombudsman physician could be assigned at the outset of consideration of a QA investigation, because the stigma that accompanies a complaint and investigation can inhibit a physician’s appropriate defenses. This ombudsman physician could act as an intermediary between administration and staff to ensure fairness and compliance with hospital bylaws in the early informal discussions about and with the surgeon, long before the need to obtain legal counsel.

- Awareness of and training to avoid these forms of bias should be part of the job to serve on an MEC. There should be leadership training that includes data interpretation at the time of appointment to these positions regarding these biases to avoid harm to colleagues while protecting patient safety. A checklist to ensure these biases have not found their way into the review should be part of the record. Moral and ethical self-checks should occur for each committee member.

CONCLUSIONS

Peer review must be perceived as a legitimate and equitable process for quality improvement. If bylaws are followed, all data is examined carefully, all evidence is admitted and studied, and individual morality is upheld, peer review can improve patient care. Participating NSQIP hospitals should provide each surgeon with their data that is accurately acquired every six months, along with comparable NSQIP database information, so that surgeons can monitor their own practices and achieve the safest standards of care.

Surgeons under review must read the bylaws of their hospitals and understand them thoroughly. Surgeons must know of and understand the databases and registries that administrators use, and how to use the data properly. Providers should retain legal assistance at the start of any peer review process so that mistakes are avoided. Due to lawyers’ and non-subspecialists’ unfamiliarity with medical and subspecialty standards, all evidence must be thoroughly examined and adjudicated for accuracy and consistency with published standards, along with explanation of their significance during peer review and provider evaluations.

NSQIP data can predict and reflect practice quality, but the current data entry variables and abstraction methods hinder subspeciality assessment for both surgeons and facilities. Abstracting all laparoscopic and abdominal cases by Gynecologists, designating subspecialty status, disease process, and recognizing what incisions/repairs are accidents or incident to the procedure, will make the NSQIP dataset more useful.

Highlights

-Accuracy and the proper use of medical registries and databases is key to quality patient care and to provider benchmarks.

-Steps to address and mitigate faulty reporting of quality patient outcomes in gynecology oncology are needed.

-Sham peer review can disrupt quality patient care with misuse of databases.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All four authors declare that they have received no outside funding for this manuscript and have no conflict of interest in its production.

REFERENCES

- Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, Barbour G, Lowry P, Irvin G, et al. (1995). The National Veterans Administration Surgical Risk Study: risk adjustment for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am College Surgeons. 180(5):519-31.

- Fink AS, Campbell DA Jr, Mentzer RM Jr, Henderson WG, Daley J, Bannister J, et al. (2002). The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in non-veterans administration hospitals: initial demonstration of feasibility. Annals Surg. 236(3):344-3553; discussion 353-435.

- American College of Surgeons. (2022). Hospital and Facilities,. American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/hospital-and-facilities/?searchTerm=&institution=NsqipHospital&address=&country=&page=1

- American College of Surgeons NSQIP. (2017). User Guide for the 2017 ACS NSQIP Procedure Targeted Participant Use Data File (PUF).

- Kiran A, Hilton P, Cromwell DA. (2016). The risk of ureteric injury associated with hysterectomy: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 123(7):1184-1191.

- Peiretti M, Bristow RE, Zapardiel I, Gerardi M, Zanagnolo V, Biffi R, et al. (2012). Rectosigmoid resection at the time of primary cytoreduction for advanced ovarian cancer. A multi-center analysis of surgical and oncological outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 126(2):220-223.

- Gillette-Cloven N, Burger RA, Monk BJ, McMeekin DS, Vasilev S, DiSaia PJ, et al. (2001). Bowel resection at the time of primary cytoreduction for epithelial ovarian cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 193(6):626-632.

- O'Hanlan KA, Kargas S, Schreiber M, Burrs D, Mallipeddi P, Longacre T, et al. (1995). Ovarian carcinoma metastases to gastrointestinal tract appear to spread like colon carcinoma: implications for surgical resection. Gynecol Oncol. 59(2):200-206.

- Awtrey CS, Cadungog MG, Leitao MM, Alektiar KM, Aghajanian C, Hummer AJ, et al. (2006). Surgical resection of recurrent endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 102(3):480-488.

- Clayton RD, Obermair A, Hammond IG, Leung YC, McCartney AJ. (2002). The Western Australian experience of the use of en bloc resection of ovarian cancer with concomitant rectosigmoid colectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 84(1):53-57.

- Scarabelli C, Campagnutta E, Giorda G, et al. (1998). Maximal cytoreductive surgery as a reasonable therapeutic alternative for recurrent endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 70(1):90-93.

- Bernard L, Boucher J, Helpman L. (2020). Bowel resection or repair at the time of cytoreductive surgery for ovarian malignancy is associated with increased complication rate: An ACS-NSQIP study. Gynecol Oncol. Sep 158(3):597-602.

- Birkmeyer JD, Hamby LS, Birkmeyer CM, Decker MV, Karon NM, Dow RW. (2001). Is unplanned return to the operating room a useful quality indicator in general surgery? Arch Surg. 136(4):405-411.

- Aletti GD, Dowdy SC, Gostout BS, Jones MB, Stanhope CR, Wilson TO, et al. (2006). Aggressive surgical effort and improved survival in advanced-stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 107(1):77-85.

- Wallace S, Kumar A, Mc Gree M, Weaver A, Mariani A, Langstraat C, et al. (2017). Efforts at maximal cytoreduction improve survival in ovarian cancer patients, even when complete gross resection is not feasible. Gynecol Oncol. 145(1):21-26.

- Barber EL, Rossi EC, Alexander A, Bilimoria K, Simon MA. (2018). Benign hysterectomy performed by gynecologic oncologists: Is selection bias altering our ability to measure surgical quality? Gynecol Oncol. 151(1):141-144.

- Benedetti Panici P, Di Donato V, Fischetti M, et al. (2015). Predictors of postoperative morbidity after cytoreduction for advanced ovarian cancer: Analysis and management of complications in upper abdominal surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 137(3):406-111.

- Chang SJ, Bristow RE. (2012). Evolution of surgical treatment paradigms for advanced-stage ovarian cancer: redefining 'optimal' residual disease. Gynecol Oncol. 125(2):483-492.

- Stewart KA, Tessier KM, Lebovic DI. (2022). Comparing Characteristics of and Postoperative Morbidity after Hysterectomy for Endometriosis versus other Benign Indications: A NSQIP Study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 29(7):884-890 e2.

- Barber EL, Doll KM, Gehrig PA. (2017). Hospital readmission after ovarian cancer surgery: Are we measuring surgical quality? Gynecol Oncol. 146(2):368-372.

- Scalici J, Laughlin BB, Finan MA, Wang B, Rocconi RP. (2015). The trend towards minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for endometrial cancer: an ACS-NSQIP evaluation of surgical outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 136(3):512-515.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Gabor L, Burke WM, Tergas AI, Hou JY, et al. (2017). Patterns of Specialty-Based Referral and Perioperative Outcomes for Women With Endometrial Cancer Undergoing Hysterectomy. Obstetrics Gynecol. 130(1):81-90.

- Casarin J, Multinu F, Ubl DS, Dowdy SC, Cliby WA, Glaser GE, et al. (2018). Adoption of Minimally Invasive Surgery and Decrease in Surgical Morbidity for Endometrial Cancer Treatment in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 131(2):304-311.

- Bochenska K, Leader-Cramer A, Mueller M, Dave B, Alverdy A, Kenton K. (2017). Perioperative complications following colpocleisis with and without concomitant vaginal hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J. 28(11):1671-1675.

- Cardenas-Trowers O, Stewart JR, Meriwether KV, Francis SL, Gupta A. (2020). Perioperative Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Sacrocolpopexy Based on Route of Concurrent Hysterectomy: A Secondary Analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 27(4):953-958.

- Hill AM, Pauls RN, Crisp CC. (2020). Addressing apical support during hysterectomy for prolapse: a NSQIP review. Int Urogynecol J. 31(7):1349-1355.

- Pepin KJ, Cook EF, Cohen SL. (2020). Risk of complication at the time of laparoscopic hysterectomy: a prediction model built from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 223(4):555 e1-555 e7.

- Chapman GC, Slopnick EA, Roberts K, Sheyn D, Wherley S, Mahajan ST, et al. (2021). National Analysis of Perioperative Morbidity of Vaginal Versus Laparoscopic Hysterectomy at the Time of Uterosacral Ligament Suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 28(2):275-281.

- Uppal S, Rebecca Liu J, Kevin Reynolds R, Rice LW, Spencer RJ. (2019). Trends and comparative effectiveness of inpatient radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer in the United States (2012-2015). Gynecol Oncol. 152(1):133-138.

- Polan RM, Rossi EC, Barber EL. (2019). Extent of lymphadenectomy and postoperative major complications among women with endometrial cancer treated with minimally invasive surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 220(3):263 e1-263 e8.

- Hanwright PJ, Mioton LM, Thomassee MS, Bilimoria KY, Van Arsdale J, Brill E, et al. (2013). Risk profiles and outcomes of total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 121(4):781-787.

- Linder BJ, Occhino JA, Habermann EB, Glasgow AE, Bews KA, Gershman B. (2018). A National Contemporary Analysis of Perioperative Outcomes of Open versus Minimally Invasive Sacrocolpopexy. J Urol. 200(4):862-867.

- Bretschneider CE, Casas-Puig V, Sheyn D, Hijaz A, Ferrando CA. (2019). Delayed recognition of lower urinary tract injuries following hysterectomy for benign indications: A NSQIP-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 221(2):132 e1-132 e13.

- Chen I, Choudhry AJ, Schramm D, Cameron DW, Leung V, Singh SS, et al. (2019). Type of Pelvic Disease as a Risk Factor for Surgical Site Infectionin Women Undergoing Hysterectomy. J Minim invasive Gynecol. 26(6):1149-1156.

- Lake AG, McPencow AM, Dick-Biascoechea MA, Martin DK, Erekson EA. (2013). Surgical site infection after hysterectomy. Am J obstet Gynecol. 209(5):490 e1-9.